This weekend I was driving through Central Florida on U.S. 301, so I just HAD to stop at the Orange Shop in Citra. It was as if my car was pulled into their parking lot by one of those giant magnets that Wile E. Coyote always used for his harebrained schemes.

The Orange Shop has been selling citrus in Citra since 1936, aided by a series of pun-filled billboards that say things like “Make Us Your Main Squeeze.” It used to have a lot more competition for us drive-by customers but most of those other citrus stands have disappeared, along with the groves that supplied them.

While the clerk was ringing up my bag of fruit, I told her I sympathized with her over the latest bit of bad news. President Convicted Felon had announced he was proceeding with his latest harebrained scheme of imposing stiff tariffs on our allies, Canada and Mexico. Canada was talking about hitting back with its own tariffs on, among other things, Florida orange juice.

The clerk didn’t miss a beat. “Means more for us!” she chirped, still upbeat about making a sale.

Then she told me that my bag of tangerines was a BOGO so I could get another bag. In other words, they were literally giving them away.

These are tough times for Florida’s citrus industry. They’ve been battered by hurricanes, disease and developers eager to convert their grove land to sprawl. Where we used to savor the sweet scent of orange blossoms, we now can smell only the raw stink of bulldozers at work.

“Of the 950,000 acres zoned for citrus in 2012, Florida lost more than half by 2023,” the Tampa Bay Times reported last month. “Last year, a major labor group representing growers shut down due to financial constraints.”

Now they’re facing a new foe: that Florida club owner in the White House. You’d think he’d be more sympathetic to the citrus industry, given how his facial coloration resembles their main product.

Yet Trump has launched a ridiculous trade war with our politest ally, which is sure to hurt the demand for Florida citrus in the Great White North. He’s also started one with Mexico that will hurt citrus processors (more on that in a minute).

Meanwhile, his immigration roundup is sure to hinder the industry’s labor supply.

Is it any wonder one of the remaining giants of Florida citrus, Fort Myers-based Alico Inc., announced last month that it’s getting out of the business?

“We determined that it’s not economically viable for us,” the CEO, John Kiernan, told Gulfshore Business. Instead, look for the company, like so many others before it, to turn to a different, less savory crop: houses.

“It’s a rather dismal time for the industry,” said Fritz Roka, director of the Center for Agribusiness at Florida Gulf Coast University. “It’s sad, because they have been such a big part of our culture.”

The most functional sentence

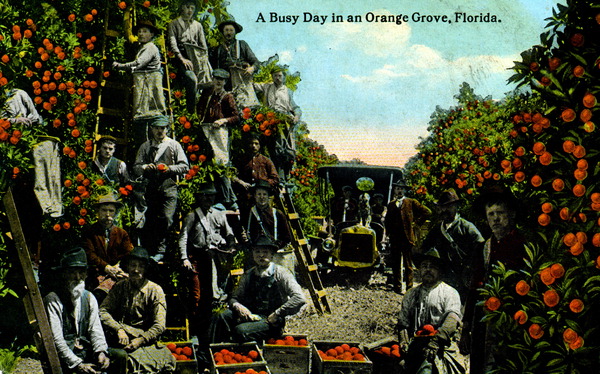

Citrus has been so important to Florida that there are counties named “Citrus” and “Orange.” There are oranges on Florida license plates. Oranges are our official state fruit, orange juice our official state beverage, and the orange blossom our official state flower.

Oranges can pop up in the strangest places. The University of Florida’s stadium is known as “The Swamp,” but it’s named for citrus magnate Ben Hill Griffin Jr. Perhaps UF should call it “The Grove.”

Yet the orange is not a native of Florida. Like two-thirds of the state’s residents (including a certain Palm Beach club owner), oranges came from someplace else — specifically, Spain.

Spanish explorers carried the fruit aboard their ships so their crews could eat them to ward off scurvy. They would plant the seeds in pots on the ship and transplant the saplings wherever they landed, according to Erin Thursby, author of “Florida Oranges: A Colorful History.”

Florida’s earliest groves date to 1565, when Spanish explorer Pedro Menéndez de Avilés founded St. Augustine. The groves the Spanish planted around the city were intended strictly for local consumption.

But by the late 1700s, a slippery St. Augustine businessman named Jesse Fish — described by one historian as a “land dealer, slaver, smuggler, usurer, and cunning crook” — found a way to send Florida oranges elsewhere. He became the first to export oranges out of state and we owe him a huge debt of gratitude (and maybe a pardon).

Harriet Beecher Stowe, who helped start the Civil War with her novel “Uncle Tom’s Cabin,” moved to a cabin in a Florida town called Mandarin after the war. You could trace the origin of both our citrus and tourism industry to her.

She wrote letters to Northern newspapers in which she extolled the state as a paradise, encouraging her readers to visit. She also claimed anyone who moved here could live off the earnings from growing citrus, even without royalties from a bestselling novel.

During World War II, the government launched a fruit-based Manhattan Project here to figure out how to ship orange juice to the troops overseas to combat scurvy. The result of that concentrated science project: frozen concentrated orange juice, which became a hit in the ’50s with families — thanks, in part, to the newfangled freezers sold as part of kitchen refrigerators.

“The most functional sentence in the English language is: Mix with three cans of water and stir,” said historian Gary Mormino, author of “Land of Sunshine, State of Dreams: A Social History of Modern Florida.”

How popular was the new product? “Citrus production in Florida increased from 43 million boxes in 1945 to 72 million in 1952,” the Florida State Archives note. “About half of all fruit became [frozen concentrate] in the 1950s.”

During the glory years of the citrus industry — the 1990s — growers harvested 240 million boxes of fruit a year. By contrast, the 2022 harvest, 41 million boxes, was the lowest since World War II. The USDA’s latest crop forecast — you know, the one so crucial to the plot of the movie “Trading Places” — predicts this season’s orange crop will be a mere 12 million boxes.

That’s a faster decline and fall than the Roman Empire’s.

The view from the tower

Near Orlando, in the town of Clermont, a couple of tourism promoters built a 226-foot spire known as the Citrus Tower. When it opened in 1956, the view it offered of the orange-filled countryside was breathtaking.

“From the top of that tower you could once see 12 to 16 billion citrus trees,” Mormino told me. “Today it’s all gone, unless you spot one growing in someone’s backyard.”

Where did the trees go? Freezes killed a lot of them. Hurricanes knocked them down or drowned them in floods. Then there were the diseases — citrus canker, then citrus greening.

Greening has been particularly destructive over the past 20 years, leaving the fruit nearly inedible and trees weaker, more likely to be toppled by high winds. I had a backyard tangerine tree that was a victim of greening, so I know this firsthand.

Now, on top of all that destruction, we’ve got the red-hatted chief MAGA of ’Merica threatening to slap 25% tariffs on Canada, with little thought to the consequences.

That has prompted Canada to threaten to slap its own tariffs on American imports. Prime Minister Justin Trudeau specifically mentioned Florida orange juice. Turns out Canada consumes a LOT of Florida OJ.

“Florida exports tens of millions of dollars’ worth of orange juice to Canada,” WLRN-FM reported this week. “About 60% of American orange juice sent to Canada comes from Florida.”

The Canada tariffs are now on hold for 30 days, but that’s not much breathing room. Meanwhile, the Mexican tariffs are more bad news for Florida’s citrus industry, Roka said. Now that Florida’s orange groves have faltered, our remaining juice processors — Tropicana, Minute Maid and Florida’s Natural — are buying much of the fruit they need from Mexico, he explained. Because tariffs are routinely passed along to the customers, guess who has to pay those higher fees?

Fortunately, that’s on hold for 30 days, too, or until Co-President Elon Musk decides it’s a bad investment.

But what’s not on hold are the widespread raids by U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement agents looking for illegal immigrants to deport.

Florida’s citrus growers have made good use of the H-2A program, which allows people from other countries to come to the U.S. to legally work jobs in the agriculture industry, Roka told me. That means that all their immigrant labor is legal immigrant labor.

But the ICE agents have been scooping people up left and right and shipping them out so quickly, they’ve had little time to check everyone’s paperwork. I’m sure they’ll eventually get it all sorted out at the detention camp at Guantanamo.

So far, it’s been worse than when the Florida Legislature passed an anti-immigration bill in 2023. So many immigrants fled the fields then that three Republican lawmakers, in a secret meeting that leaked out, protested that their bill was just meant to scare people, not actually shut down farm operations.

Free cups of olive oil

I tried repeatedly to reach some folks in the citrus industry who would talk to me about all this. Although a spokesperson for the trade association known as Florida Citrus Mutual insisted there were signs of hope for the future, she couldn’t give details and nobody else wanted to explain.

Some citrus growers are trying to hang on by switching to different crops, such as olives, pomegranates, peaches, avocados, or even hops. Before you rush out and start printing up a bunch of “I Hop for Beer from Florida Hops” bumper stickers, I should tell you that those alternatives have so far not proven to be as successful as OJ.

In other words, don’t hold your breath for the Florida Welcome Center to switch from offering free cups of orange juice to cups of olive oil (and a little piece of bread to dip in it).

The thing of it is, every time a citrus grower even thinks about giving up the fight, a developer’s right there with a big check, ready to take over that high and dry, well-drained property. The next step: Pave it over and send the stormwater cascading onto its rural neighbors.

I called up the folks from the smart growth organization 1000 Friends of Florida to ask what they think we should do about our disappearing citrus industry.

“It’s sad to watch the shift in Florida’s identity,” said Kim Dinkins, the organization’s policy and planning director. “But it’s an opportunity for us to do better.”

Local governments that have citrus groves classified as rural and agricultural areas should stick to those zoning designations, she said. Unless and until the infrastructure — water lines, sewer lines, roads etc. — are put in place to handle any development, there should be no change.

If and when development is allowed to replace another orange grove, she said, it should not be the cookie-cutter, one-size-fits-all kind we’ve seen all over the place (and probably called “The Citrus Stand” or “The Fruit Trees”).

Instead, she called for development that’s clustered instead of sprawling, with large conservation areas that are preserved by a permanent easement and low water-use lawns and landscaping required.

I’m sure a lot of developers will object to such common-sense constraints, but here’s hoping that local elected officials heed that sound advice, because it’s important for our quality of life here.

Speaking as someone who routinely enjoys a cup of OJ with my breakfast, I, too, will be sorry to see oranges, orange blossoms, and orange juice fade away into the sepia tones of ancient Florida history.

But hey, it’s not like we can afford to pay for juice AND our super-expensive eggs.

_________

Florida Phoenix reporter Craig Pittman authored this report.

Post Views: 0

Entertainment8 years ago

Entertainment8 years ago

Entertainment8 years ago

Entertainment8 years ago

Politics8 years ago

Politics8 years ago

Tech8 years ago

Tech8 years ago

Tech8 years ago

Tech8 years ago

Tech8 years ago

Tech8 years ago

Politics8 years ago

Politics8 years ago

Tech8 years ago

Tech8 years ago