Business

How the US is playing a ‘big game of catch-up’ in the Arctic

Throughout the Trump administration’s monthslong exercise in escalatory rhetoric surrounding the president’s ardent desire for Greenland, a key throughline has emerged. Rather than a bid for the mineral wealth buried in the Arctic island, which is semi-sovereign and administered by Denmark, Trump and U.S. officials have framed the territory as critical to entrenching the U.S.’s strategic seniority in the far north.

Trump’s envoy to Greenland, his press secretary and his vice president have all recently argued that this is a foreign-policy play. “American supremacy in the Arctic is non-negotiable,” Jeff Landry, Louisiana governor, recently wrote in the New York Times, while Karoline Leavitt called Greenland “vital” for deterring America’s “adversaries in the Arctic.” JD Vance said it in March: “We need to ensure that America is leading in the Arctic, because we know that if America does not, other nations will fill the gap where we fall behind.”

Kenneth Rosen, an experienced war correspondent who has covered conflicts from the Middle East to Ukraine, has spent two years traveling around the Arctic Circle, reporting from military bases, indigenous communities and ice-breaking, and he told Fortune he thinks the U.S. has “neglected the north for a long time.” As he reports for his new book Polar War, he said he sees “a big game of catch-up happening, and the U.S. is not doing what it needs to to catch up.”

The problem, Rosen said, is that the Arctic’s leadership power vacuum has already been filled, and for the U.S. to catch up now would be a monumental undertaking. And while Trump’s push for Greenland may be an attempt to reverse that status quo, the bellicose rhetoric may be dealing even more harm to the U.S.’s ambitions in the Arctic.

Polar War: Submarines, Spies, and the Struggle for Power in a Melting Arctic, was published by Simon & Schuster in January. It simultaneously reads as a geopolitical thriller, travelogue and environmental meditation, with Rosen describing the delicate state of affairs up north, where higher temperatures and retreating sea ice have revealed new possibilities for transpolar navigation and resource extraction.

The pole’s new reality has set in motion a great power struggle between the U.S., Russia and China. Change is happening at anything but a glacial pace in the Arctic, Rosen writes, and the U.S. is barely keeping up with its competitors.

Trump’s ice-covered jewel

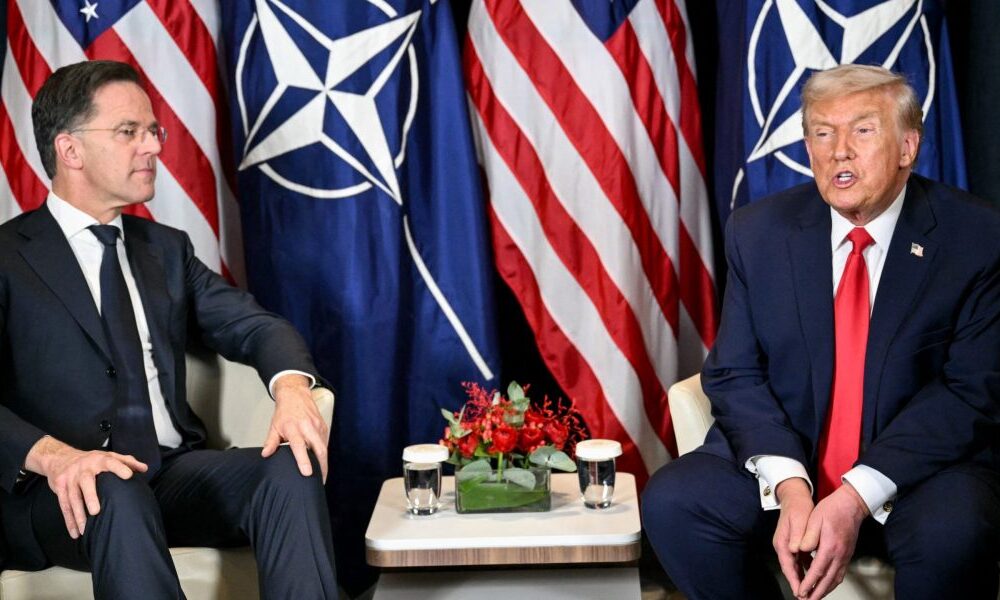

On January 21, the world watched as U.S. President Donald Trump delivered a much-anticipated speech in Davos, Switzerland, in which he reiterated his desire for control of Greenland, an ultimatum that has cast into doubt the terms of Europe’s relationship with the U.S., the state of the NATO alliance, and whether the U.S.-led global order is still alive at all.

But American obsession with Greenland has long predated Trump. In his book, Rosen describes Greenland as America’s “ace-in-the-hole,” given the territory hosts the country’s northernmost military base. Before Trump, the U.S. had attempted to purchase Greenland three times, and public intellectuals have long considered the island under the purview of America’s security blanket as defined by the Monroe Doctrine, famously resuscitated by Trump in 2026.

The island is seen as a crucial shield standing between Russia, China, and the U.S.’s East Coast, as well as close western European allies and maritime trade in the Atlantic. In Trump’s speech at Davos, he described Greenland as “right smack in the middle” between the U.S. and its rivals. China in particular has attempted inroads in Greenland in recent years, Rosen writes, including efforts to construct three airports on the island and to purchase a former American naval base in the southwest corner of the island.

But in trying to bully his way into Arctic superpower status, Trump may be undermining America’s influence in the region, Rosen argued. By hosting U.S. military and aligning with American strategic interests, Greenland, “is already an American partner in all the ways that matter,” he writes, and the bombast of Trump’s recent rhetoric may be self-defeating.

“Ever since the conversation turned to Greenland, there’s been this worry that what momentum we had in reengaging our confidence in the Arctic is now being lost,” Rosen told Fortune. “As long as we continue to berate the European Union and Nordic and Scandinavian nations, we’re just going to push ourselves farther and farther away from a beneficial place in the Arctic.”

What makes matters worse, for the U.S. at least, is that its presence in the Arctic is almost entirely based on its ability to cooperate with European allies, Rosen said. While Russia and China have dedicated significant resources to beefing up their own security position in the Arctic, America has fallen woefully behind.

America’s ‘sclerotic response’

Take icebreakers, a special-purpose ship designed to withstand and navigate ice-covered waters. Russia has more than 50 of these vessels. China, which dubs itself a “near-Arctic state,” has at least four. The U.S. has two, one of which has endured multiple mechanical fires and canceled voyages in the past few years.

Another gap is visible in military bases. Over the past few decades, Rosen writes, Russia has reopened and modernized more than 50 Cold War-era installations scattered along its Arctic coastline, including radar stations, airforce bases and self-sufficient military outposts. The U.S. currently has 10 bases in Alaska and, for the moment, one in Greenland.

In his book, Rosen describes the U.S. strategy as a “sclerotic response” to the reality of the situation in the Arctic. The cornerstone U.S. initiative to reassert its Arctic presence has been the Polar Security Cutter program, which plans to deploy a modernized fleet of three new ice-faring vessels. But the program is nearly a decade behind schedule and around 60% over budget, the Congressional Budget Office reported in 2024. As one former diplomat told Rosen: “A strategy without budget is hallucination.”

The fact that the U.S. is even talking about an Arctic strategy is a step forward, Rosen said, and efforts to modernize Alaska’s military bases and deepwater ports are important. But Trump’s bombast over Greenland risks distancing the U.S. from its NATO allies that provide surveillance, cold-weather and ship-building expertise, and form a stronger collective deterrence against Russia.

“The Trump administration has been really bad about using soft power, leveraging soft power to benefit national security,” Rosen said.

In the meantime, Russia and its broad strategic partnership with China in the Arctic risks leaving the U.S. behind. In some ways, the race might already have been won. When asked whether he sees the Arctic as being on the cusp of war, Rosen demurred somewhat. The region might not play host to a traditional war, fought with guns, infantry and mass casualties. Rosen says a “gray-zone” suite of covert tactics are more likely to be deployed in the Arctic. These can include sabotaging infrastructure to foment unrest, subtly interfering with training exercises to undermine Arctic capabilities, and exploiting divisions in adversarial alliances.

Russia is likely already doing all of those things. NATO countries have repeatedly accused Russia of damaging undersea electrical cables and gas pipelines and jamming civilian and military air signals. Rosen recounts a 2023 Russia-backed scheme to rush its Finnish border with multiple waves of undocumented migrants from third countries, ostensibly to scramble its security resources and ratchet up domestic debate over illicit immigration.

Rosen calls this strategy one of “discombobulation,” a deliberate effort to keep rivals in the dark and constantly guessing. And for now, when it comes to the great power race in the Arctic, discombobulation appears to be winning.

“Russia is basically saying, ‘We’ve already been here. We are here and you guys have no stake in it the way we have a stake in it. So you have to follow our lead.’”