Business

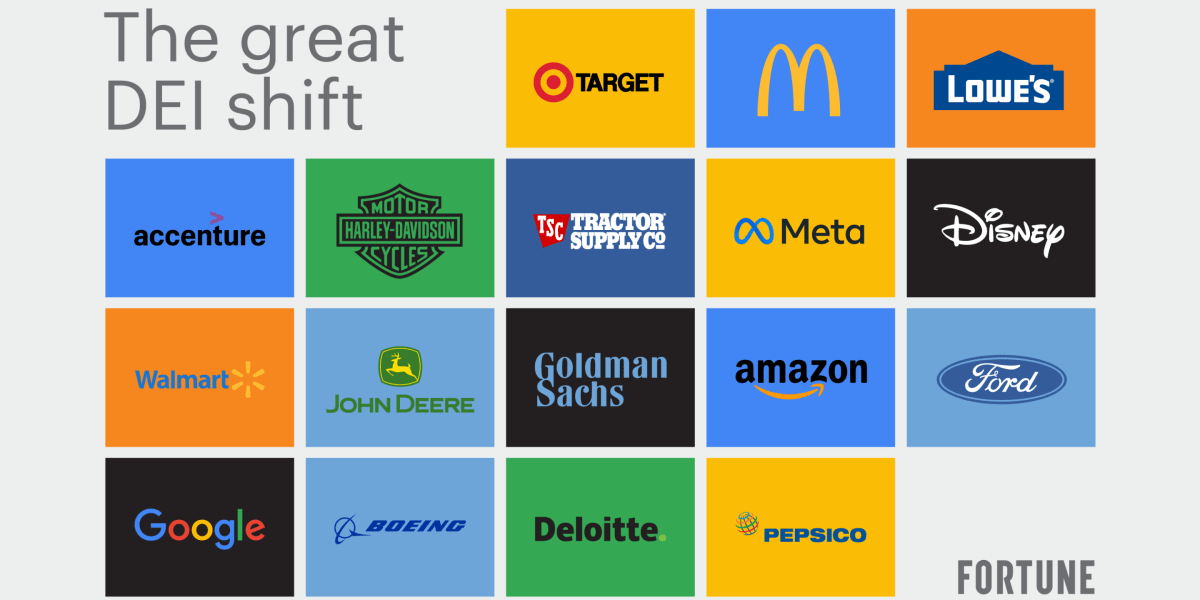

Fortune 500 comopanies like Meta and Target are rolling back DEI—These are the policies they’re changing

Published

4 hours agoon

By

Jace Porter

© 2025 Fortune Media IP Limited. All Rights Reserved. Use of this site constitutes acceptance of our Terms of Use and Privacy Policy | CA Notice at Collection and Privacy Notice | Do Not Sell/Share My Personal Information

FORTUNE is a trademark of Fortune Media IP Limited, registered in the U.S. and other countries. FORTUNE may receive compensation for some links to products and services on this website. Offers may be subject to change without notice.

You may like

Business

Trump delays Canada, Mexico tariffs for goods under USMCA

Published

27 minutes agoon

March 6, 2025By

Jace Porter

© 2025 Fortune Media IP Limited. All Rights Reserved. Use of this site constitutes acceptance of our Terms of Use and Privacy Policy | CA Notice at Collection and Privacy Notice | Do Not Sell/Share My Personal Information

FORTUNE is a trademark of Fortune Media IP Limited, registered in the U.S. and other countries. FORTUNE may receive compensation for some links to products and services on this website. Offers may be subject to change without notice.

Business

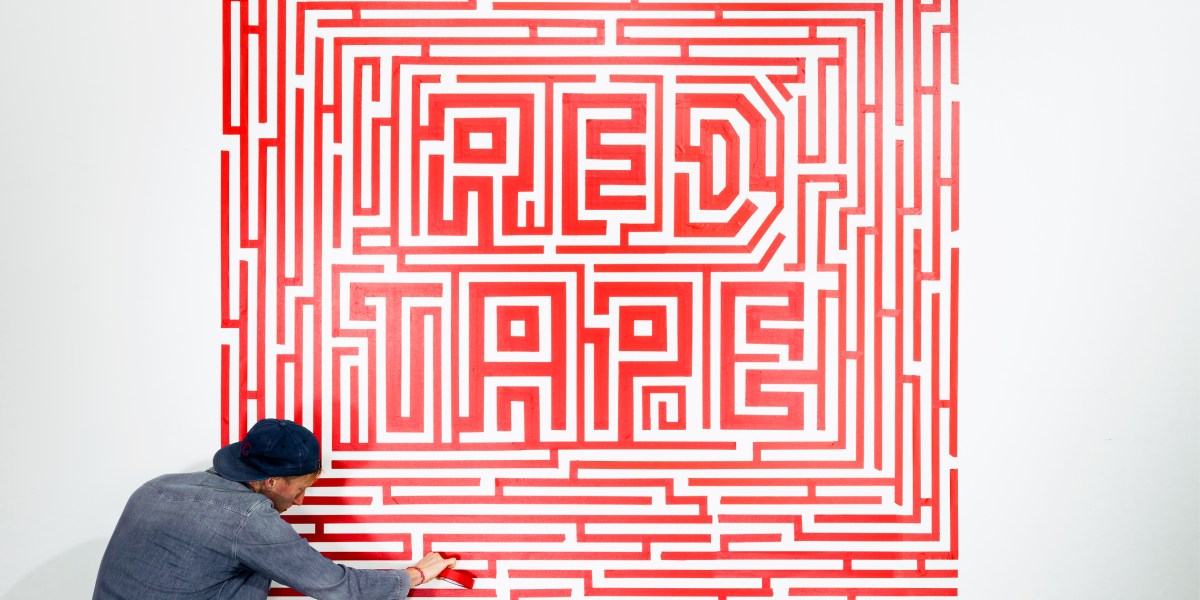

The Red Tape Conundrum (Fortune Magazine, Nov. 2016)

Published

2 hours agoon

March 6, 2025By

Jace Porter

It may well be the biggest bogeyman in business—bigger, perhaps, than even taxes: We’re talking, of course, about red tape. The idea that burdensome and overly complicated government regulation is strangling growth is almost as old as commerce itself. But right now the hue and cry from the business community is louder than at just about any time in recent memory.

Concern about regulation is soaring among executives. In a recent survey by Deloitte, North American chief financial officers named new, burdensome regulation as the No. 2 threat to their business, behind only the possibility of a recession. When the National Federation of Independent Business, which represents 325,000 small U.S. companies, conducted its quadrennial survey earlier this year, its members identified “unreasonable government regulations” as the second-biggest threat, after rising health care costs. And for a fourth year in a row, the CEOs surveyed by the Business Roundtable for its annual economic outlook cited regulation as the top cost pressure facing their companies.

Red tape has emerged as a major talking point in the presidential campaign—with each candidate approaching the topic in characteristic fashion. Hillary Clinton has promised to be the “small-business President” and has wonkishly outlined plans to cut red tape by streamlining the startup process for entrepreneurs and expanding access to credit through community banks and credit unions.

For learn more about red tape, watch this Fortune video:

[fortune-brightcove videoid=5177290154001]

Donald Trump, meanwhile, has taken a more shoot-from-the-hip approach. The Republican nominee has vowed to roll back many of the new regulations enacted under President Obama, including environmental standards designed to address climate change. Trump’s campaign has proposed a 10% overall reduction in regulations. But the candidate himself has at times suggested a more sweeping overhaul. On the same day that a videotape from 2005 surfaced showing Trump bragging about his aggressive sexual behavior—a revelation that sent his poll numbers crashing—the nominee cavalierly told a crowd at a town hall in New Hampshire that he would eliminate the majority of federal agency regulations if elected. “I would say 70% of regulations can go,” Trump said. “It’s just stopping businesses from growing.”

For more on where the Hillary Clinton and Donald Trump stand on regulation, click here.

Red tape is clearly a major source of friction—but is it really strangling business? The answer is less obvious than it may seem. For a phenomenon that’s seemingly ever present, red tape can be harder to pinpoint than you might think. Weighing the costs of regulations against their benefits is not always a straightforward task. How do you tweak your model, for example, to account for slowing down a global-warming Armageddon? Or fully account for the stability—and transparency—that keep your financial markets healthy?

Even economists who believe that the system is flawed have a hard time quantifying the issue. “I do think that our economy loses resilience and adaptability because the regulatory structure is so rigid,” says Michael Mandel, chief economic strategist at the center-left Progressive Policy Institute and one of Washington’s top thinkers on regulatory reform. “I would say that our sluggish growth is partly connected with regulation. But it’s hard for me to put a number on it. And God knows I’ve tried.”

We can certainly intuit the drag of bureaucracy—in the increasingly long and expensive process of developing new medications, for instance. And there are endless examples of how, in isolation, red tape appears to cost us plenty. Infrastructure projects that get delayed for years—with tens of thousands of pages of environmental reviews and permits—resulting in millions in extra costs.

The U.S. remains a friendly market relative to most countries, but there are signs of slippage. In its “Doing Business 2016” report, which assesses economies around the globe by regulatory efficiency, the World Bank ranked the U.S. at No. 7, down from No. 4 five years ago. America came in below Hong Kong and the United Kingdom (No. 5 and No. 6 respectively) but ahead of Germany (No. 15).

In a bigger sense, a growing number of observers worry that our 20th-century regulatory system may be unfit for an increasingly complex and fast-changing world. How can we be sure that our regulatory framework promotes innovation and fosters growth while at the same time protecting workers and consumers? Can we fix the current system or do we need to start over? And how much is business at fault for the very excesses that companies themselves bemoan? Heck, where does red tape even come from, and how is it gumming up the works? And, finally, is there anything anybody can do to stop it?

Fortune set out to explore those questions and more in recent weeks—through dozens of interviews with CEOs, investors, researchers, academics, economists, and policy experts—and tried not to get knotted up in the process.

![]()

First, we offer a very brief history lesson: The phrase “red tape” in English goes back hundreds of years. It originally referred to the red ribbons that were used to bind up important legal documents. By the time of Dickens, the term had become synonymous with the idea of bureaucratic waste and inertia. (Lesson over.)

How exactly do we define red tape today? The idiom is ubiquitous, but the meaning is mushy for most people. Not so for Barry Bozeman, the director of the Center for Organization Design and Research at Arizona State University and one of the academic world’s leading experts on the topic. He offers this definition: “rules, regulations, and procedures that have a compliance burden but do not achieve the functional objective of the rule.”

In Bozeman’s mind this leads to a crucial distinction. “The first problem that people usually run into when they’re asking about red tape is that they’re asking about the wrong thing,” says Bozeman, coauthor of an influential 2011 academic treatise called Rules and Red Tape. “Because red tape and rules are not the same thing. You can have one rule and it can be nothing but terrible red tape if it doesn’t accomplish a goal. Or you can have a bunch of rules that are incredibly effective, and none of them would be red tape.”

Companies are certainly more than capable of creating their own bureaucracies, and do. But when business leaders complain about red tape, they’re almost always griping about government regulations.

Lately, much of that grumbling has been directed toward President Obama. There is growing frustration in the business community about the amount and ambitious scope of new federal regulations being produced by his administration. In the first installment of a six-part look back at his presidency, the New York Times, hardly a stalwart of conservatism, called Obama “the Regulator in Chief” and asserted that he will leave office as “one of the most prolific authors of major regulations in presidential history.”

The numbers bear that out. A total of 560 major regulations—those having an economic impact of $100 million or more—were published in the first seven years of the Obama administration, according the George Washington University Regulatory Studies Center, compared with 494 for his predecessor, George W. Bush. And the number of new rules passed typically spikes in a President’s final year in office.

Two major new sources of regulations under Obama were the landmark laws enacted in 2010: the Dodd-Frank bill, a massive response to the financial crisis of 2008, and Obama’s signature Affordable Care Act, the contentious law that brought health care to millions of uninsured Americans. (The law firm Davis Polk calculated last year that the more than 22,000 pages of rule releases related to Dodd-Frank added up to more than 34 copies of Moby Dick.) But with Congress unable to pass much of anything in recent years, the President has empowered his executive branch to pursue policy goals ranging from the battle against climate change to improving workplace safety.

Ask Big Business whether these are rules or red tape and you’ll get a full-throated answer: “The CEOs of the Roundtable absolutely would say that one of the reasons that GDP is limping along where it is, in the 1% or 2% range, is the oppressive regulations that have been unrelenting in the past several years,” says John Engler, a former Republican governor of Michigan and the president of the Business Roundtable. “I just think that people have almost thrown up their hands. What we have is an equal opportunity offender here, because in pretty much every agency something is going on.”

To others, that kind of complaining is par for the course from the business community. “You can go back to really 100 years now of Chicken Little claims from business about regulation,” says Robert Weissman, president of Public Citizen, the nonprofit consumer-rights advocacy group founded by Ralph Nader in the early 1970s. “Every time business has said, ‘The sky is going to fall,’ and amazingly it never does.” He cites a litany of examples—from the first rules to eliminate child labor through the New Deal to the beginning of modern environmental regulation in the 1970s and up to the adoption of smoke-free restaurants and bars.

Obama took office vowing to cut red tape rather than add to it. He installed his friend Cass Sunstein, a law professor and an author, as the administrator of the Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs (OIRA), a division of the Office of Management and Budget tasked with assessing the validity of new regulations issued by cabinet agencies. During his tenure from 2009 through 2012, Sunstein instituted a program of “retrospective review” to examine existing regulations for effectiveness. But despite much fanfare, a relatively small portion of rules have faced scrutiny under the process. Meanwhile, the rulemaking machine has continued apace.

In that way, Obama continued a long tradition of Presidents attempting—and largely failing—to control proliferation of regulations. Jimmy Carter, for instance, signed the Paperwork Reduction Act into law in 1980, creating OIRA. A year later, Ronald Reagan signed an executive order compelling cost-benefit analysis of all major regulations. Bill Clinton built on that in 1993 when he issued executive order 12866, which required every “significant regulatory action” be submitted to OIRA for review. George W. Bush then added new requirements for review with his own executive order in 2007. And still, inevitably, the total volume of rules has continued to increase.

![]()

Dr. Cynthia Deyling believes in regulation. As the chief quality officer for the Cleveland Clinic, a world-renowned nonprofit hospital system, it’s her job to keep the medical organization’s facilities—including its outposts in Florida, Nevada, Canada, and the United Arab Emirates—in compliance with the dozens of regulators that monitor its operations. Regulation, she says, “makes our organization better.” That said, she has to deal with an enormous amount of red tape—and it’s growing all the time.

The past 10 years have seen a very significant increase in regulations for hospitals, says Deyling, and in the same period the rules have become much more prescriptive and survey based. For a hospital to receive payment from Medicare or Medicaid, it must, among other things, be compliant with a range of conditions set forth by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, or CMS. Previously staff members had more discretion in exercising professional judgment. That’s been replaced, she says, with checklists and audits.

This approach has contributed to rising costs. Whereas most hospitals used to have one professional to look at risk management, the Cleveland Clinic now has 90 full-time employees at its different facilities who oversee “regulatory survey readiness.” Last year the Cleveland Clinic was subjected to 320 survey days. The hospital pays $15.5 million annually in labor and consultants to help its workers drill for the inspections. The hospital is subject to regulators including OSHA, the EPA, the Nuclear Regulatory Commission, the National Institutes of Health, and the Cuyahoga County food inspector. It’s not uncommon, says Deyling, for a nongovernmental agency to do a survey on behalf of CMS, and then for the Medicare and Medicaid agency to conduct a validation survey, only to get a different result.

Better alignment between state agencies and the federal government would save the hospital time, money, and effort. “Regulation is important and benefits patients,” says Dr. Anthony Warmuth, the Cleveland Clinic’s enterprise quality administrator. “It’s just when it goes outside the norms that seem constructive—or when it’s contradictory to other rules out there—that it creates a lot of tail chasing and it gets very confusing for us to do the right thing and comply.”

Most of the time, regulation begins with a noble goal. Laws are typically passed with the intention of addressing or preventing some wrong, and rules are developed to implement those laws. In that way, as Herbert Kaufman noted in his seminal 1977 book, Red Tape: Its Origins, Uses & Abuses, “one person’s red tape may be another’s treasured procedural safeguard.” It’s when you add up all those rules that you get into trouble at times.

Read about four industries where technology is racing ahead of regulation here.

Mandel of the Progressive Policy Institute has introduced a metaphor—one that was often repeated to me by others—to describe the effects of regulatory accumulation. It’s like throwing pebbles in a stream, the economist says. Toss one in, or even two or three, and there’s no obvious effect. But once you throw in a hundred you may start to block the flow of water. “It’s really about taking degrees of freedom away from businesses,” he says.

This is compounded by the fact that the rulemaking machinery—just like the law-making system—is geared toward pushing out new regulations, not removing them. And once new rules are on the books, they usually just stay there. Mandel points out that there is no central place in the federal government where you can report problems with regulations. And because there’s no database of complaints, there’s no way to analyze the patterns and identify overlaps that need addressing.

“I kind of think of the regulatory issue as people basically saying in their own varying ways, ‘Who’s in charge here?’ ” says Mandel. “Is there anybody who’s really steering the ship? If you point out to somebody that there’s a problem, is there anybody that can respond?”

Business leaders complain about the specter of new, onerous regulations. But when pressed, executives often have a hard time coming up with existing rules they would like to have repealed. In part, that’s because big companies are quick to adjust, and regulations that are in place become a barrier to entry for competitors.

Indeed, government intervention can be a welcome protection at times. Sprint CEO Marcelo Claure praises the Obama administration for helping his company negotiate reasonable roaming rates with Verizon and AT&T in areas where Sprint doesn’t have cell towers, and says that consumers have been the winners. “In this case we welcome regulation that doesn’t allow Verizon and AT&T to use their market power to basically drive us out of business,” Claure told Fortune in September.

![]()

Large increases in federal regulation often come in response to upheaval. The Securities and Exchange Commission, as well as much of the modern framework for modern financial regulation, was created in response to the Crash of 1929. The social and environmental awakening of the 1960s led to a desire to protect our planet, consumers, and workers, and to a great expansion of the regulatory state in the 1970s. (And that expansion, in turn, begat the Washington lobbying mega-complex.)

The attacks of Sept. 11, 2001, then prompted the creation of the Department of Homeland Security, which, with a fiscal 2016 budget of $27 billion, now accounts for 43% of the government’s spending on regulations.

Likewise, the passage of Dodd-Frank—which created a powerful new agency called the Consumer Federal Protection Bureau—was a direct response to the Great Recession. At 849 pages, it was a mammoth and ambitious statute, designed to rein in big banks and compel them to maintain higher levels of capital. Core to the legislation was the Volcker Rule, which sought to rebuild the wall between traditional and investment banks that had been erected in 1933 with the passage of the Glass-Steagall Act and torn down with its repeal in 1999.

The financial industry has bristled at the regulatory burden of Dodd-Frank since its passage. There’s no doubt it has added significant costs to the operations of big banks. In his annual letter to shareholders earlier this year, for instance, JPMorgan Chase CEO Jamie Dimon reported that since 2011 the number of employees dedicated to regulatory “controls” at the bank had risen from 24,000 to 43,000 and the yearly cost associated with that compliance effort had jumped from $6 billion to $9 billion. Of course, any compliance expenses pale in comparison to the cost of the financial crisis, which economists at the Dallas Fed calculated conservatively a few years ago to have been anywhere from $6 trillion to $14 trillion.

But whether all the added regulatory burden of Dodd-Frank really keeps us safer from the next financial meltdown is open to debate.

The law isn’t just an exemplar of regulatory kudzu, however. It’s also a case study in how Big Business—and big lobbying—plays a role in creating its own red tape. Consider the Volcker Rule, which was instituted to prevent banks from using customers’ money for proprietary trading. The original draft of the rule was very short, points out Dennis Kelleher, the CEO of the nonprofit advocacy group Better Markets. The final regulation ended up being 950 pages.

“Now, why is that?” asks Kelleher, a former Skadden Arps attorney who was chief counsel for Sen. Byron Dorgan (D-N.D.) during the financial crisis. “Primarily because of the financial industry. The industry lobbied over and over and over again for this exception, that exception, this clarification, this interpretation, this permitted activity. Almost all of the length in these rules are demanded by the industry—and then they complain about the length and complexity of the rule.”

To read more on how one small business owner is dealing with regulation, click here.

It’s a phenomenon that Lee Drutman has seen again and again. A senior fellow at the nonpartisan think tank New America and the author of The Business of America Is Lobbying, Drutman says that complicated regulations provide cover for the powers that be. “Once you get a benefit, you pay a lobbyist to keep that benefit,” says Drutman. “That’s why it’s so hard to simplify anything.”

Even the process of churning out the rules themselves is becoming more challenging. In June, Public Citizen published a report called Unsafe Delays that found the time it takes to complete a rule has risen sharply over the past few years. Economically significant rules completed in the first half of 2016, the nonprofit’s research found, took an average of 3.8 years, or 58% longer than the historical average. In other words, there’s a record amount of red tape in making the red tape. “You’re basically talking about an entire presidential term to get a rule through,” says Public Citizen CEO Weissman, “which makes it pretty hard to administer these things.”

The friction in the system only adds to the left-right divide on solutions. Where conservatives see a bloated regulatory state that has run amok, progressives perceive a broken system that has been hijacked by corporate interests who shape and delay regulations as much as possible.

“It’s sort of weird,” says Sam Batkins, the director of regulator policy at the center-right non-profit American Action Forum. “You’ll go to a meeting on regulation from the right and you’ll hear about a broken process. And you go to a regulatory meeting on the left and you also hear about a problematic process. So in that sense there is some unanimity.”

![]()

Philip K. Howard has spent more than two decades waging a campaign against red tape. But despite a marked lack of progress, it doesn’t occur to Howard, 68, to abandon his crusade. “I was talking to somebody about this the other day. People ask me, ‘Why are you beating your head against the wall?’ ” he says, and pauses. “It’s a good question.”

A prosperous New York City attorney who today is senior counsel at the white-shoe firm of Covington and Burling, Howard became alerted to the dysfunction of modern government in the early 1990s through his volunteer work in civic affairs. Since then he has written four books assailing over-legalization and founded a nonprofit, nonpartisan organization called Common Good to advocate reform—enlisting in his projects retired politicians from both the left and the right, including former senators Bill Bradley and Alan Simpson and former Indiana Gov. Mitch Daniels. Howard has appeared on The Daily Show, given a TED talk that has gotten more than half-a-million views, been a special adviser to the SEC on regulatory reform, and worked with Al Gore on his “reinventing government” project.

Howard’s belief is that our laws have gotten too precise for such a complex world and that our attempts to dictate every aspect of human behavior through rulemaking are only bogging us down. The system, he argues, is unadaptable. Similar to Mandel, Howard believes that too many different authorities means that nobody is in charge.

In recent years Howard has focused much of his energy on proposing ways to speed up the process of rebuilding America’s decrepit infrastructure. To do so, he believes, we need to radically rethink our permitting system. One of Howard’s favorite case studies is the ongoing project to raise the Bayonne Bridge to allow today’s bigger container ships into Newark Harbor in New Jersey. The plan had minimal environmental impact because it used the same right of way as the old structure and the existing foundations. Yet the approval process took more than four years and generated thousands of pages of reports, including a survey of all nearby historical buildings, adding hugely to the bill for taxpayers.

Howard has floated a three-page legislative proposal that he believes could cut the average permit time for major projects down from a decade or more to one or two years. His big idea is to empower the chair of the Council on Environmental Quality. That official, who reports to the President, would be able to decide when a project has had enough sufficient review and give it the green light. “Right now, no one has that responsibility,” says Howard, “so reviews become 20,000 pages when they should probably be 50.”

Want to start a taco truck in NYC? Here are all the rules you’ll have to know.

Washington has already addressed the issue of infrastructure delays—in a very Washington way. In December 2015, President Obama signed into law the Fixing America’s Surface Transportation Act, or FAST Act, which will create a new federal agency, a unit of the Transportation Department called the National Surface Transportation and Innovative Finance Bureau. The DOT’s recent “mile markers” report on the FAST Act doesn’t show that any funding projects have been accomplished yet, but it does list 69 new regulations, memoranda, and guidelines documents that have been issued. “It’s like something out of Gilbert and Sullivan,” says Howard.

In Howard’s mind, it’s time to go to a clean sheet of paper and rethink our entire approach. He looks to the examples of the Byzantine emperor Justinian and Napoleon, who rewrote the laws when they became too convoluted. “You can’t reform this system,” says Howard. “You have to rewrite it. That’s the lesson of history.”

![]()

Indeed, in many ways the challenge of red tape seems more urgent than ever. It is not just the sheer mass of it or the cost of it—it’s because of the transformative era in which we live. The pace of technological change is more rapid than ever, it seems, as new business models, platforms, and applications flood the marketplace.

We are in the midst of a new Industrial Revolution that will be driven by technologies such as genetic engineering and drones—and that will drive us around in autonomous vehicles. The fear is that lawmakers and regulators, in trying to keep up with these fast-moving changes, will do something to slow them down.

The Progressive Policy Institute’s Mandel worries about red tape stifling innovation in ways that we don’t even see. As an example, he offers arguably the biggest consumer technology breakthrough of the past decade—the smartphone. Mandel points out that when Apple partnered with AT&T to bring out the first iPhone in 2007, the companies were able to negotiate their original deal for the uniquely data-heavy iPhone, including an unlimited data plan, without regulators looking over their shoulders. “Suppose that you’d had to have hearings? And how long it would have taken, and how many objections would there have been?” asks Mandel, exploring the hypothetical. “How much growth would have been lost by that?”

Companies at the leading edge of this revolution have struggled at times to adapt to the entrenched regulatory state. Ride-hailing giant Uber raced ahead and built a global brand while alternately ignoring and battling regulators in many markets, with combative CEO Travis Kalanick leading the fight. Earlier this year the startup signaled that it was ready to take a different tack, forming a policy board that includes Ray LaHood, a former head of the Department of Transportation, to work with authorities on its regulatory challenges.

The fact that Uber has already secured a valuation of more than $60 billion from its venture capital investors may prove that an improvised approach can work in the right circumstances. But it’s too haphazard to build a strategy around. What companies really need is a way out of this morass.

Matt Harris is a managing director at Bain Capital Ventures who invests primarily in fintech, the emerging sector of startups that are using technology to disrupt the financial industry. “If I could change one thing, it would just be, give me one regulator,” says Harris. He points out that a payments company today needs to deal with 50 states, different parts of the Treasury Department, the FDIC, the Fed, and the Department of Justice if it plans to do anything international. In all, says Harris, there might be close to 80 different regulators watching over your business.

He acknowledges that the activity of moving money around needs to be carefully scrutinized. “But the notion that you should have 75 constituencies, all of whom on any given day can shut you down—it’s just hugely inefficient,” he says.

Having a single regulator with such sweeping authority may not be quite realistic in an economy as varied and complex as ours, however. What we really need is a new framework for thinking about regulation itself, not the regulators.

Mandel says the current system of retrospective review hasn’t made an impact. Along with Diana Carew, a colleague of his at PPI, he has proposed the formation of a Regulatory Improvement Commission that would be authorized by Congress for a fixed period to identify regulations that should be eliminated or changed to encourage innovation. A version of the proposal has been introduced in the Senate and House in the past couple of years, but has yet to gain traction.

Harris echoes Philip K. Howard in suggesting that we may need a more radical approach. The best way to respond to our increasingly complex world is to make our rules simpler, he suggests, not more detailed. Regulations are now written in an attempt to legislate every imaginable action by individuals on every imaginable subject—an impossible task. “I think the whole thing needs to be rethought and boiled back to more of a principles-based set of detailed prescriptions on how everything can work,” says Harris. “Things may fall through the cracks at times, but the approach we have now is getting creakier and creakier.”

Ironically, the very idea of red tape might be on a collision course with the forces of disruption. The technology industry has set its sights on bureaucracy, just as it has so many other hidebound, change-resistant industries before it.

As a case in point, IBM (IBM) agreed in late September to buy consulting firm Promontory Financial Group, which specializes in financial regulation. The idea is to marry Promontory’s expertise with the AI power of IBM’s Watson and develop smarter compliance systems.

David Kenny, who runs IBM’s Watson business, sees opportunities for similar investments in everything from FDA compliance to traffic rules for autonomous vehicles. “There is such a regulatory burden on companies today,” says Kenny. “All this well-meaning red tape can get in the way of progress. So if we can automate the red tape, make it clear, and help the policymaker and the folks that have to implement it better understand each other, boy, that really frees up a lot of capacity.”

After all, humans haven’t been able to eliminate red tape. We might as well let the computers have a try.

A version of this article appears in the Nov. 1, 2016 issue of Fortune with the headline “Red Tape.”

This story has been updated. An earlier version stated incorrectly that China ranked No. 5 in the World Bank’s “Doing Business 2016” report. In fact, Hong Kong ranked No. 5 and China ranked No. 84.

Business

This one dietary shift can lower your risk of cancer and heart disease

Published

2 hours agoon

March 6, 2025By

Jace Porter

© 2025 Fortune Media IP Limited. All Rights Reserved. Use of this site constitutes acceptance of our Terms of Use and Privacy Policy | CA Notice at Collection and Privacy Notice | Do Not Sell/Share My Personal Information

FORTUNE is a trademark of Fortune Media IP Limited, registered in the U.S. and other countries. FORTUNE may receive compensation for some links to products and services on this website. Offers may be subject to change without notice.

Galderma to discuss U.S. tariffs with retailers, sees “moving target”

An Oct. 7 survivor’s story moves hearts in Tallahassee

Trump delays Canada, Mexico tariffs for goods under USMCA

Trending

-

Entertainment8 years ago

Entertainment8 years agoThe final 6 ‘Game of Thrones’ episodes might feel like a full season

-

Entertainment8 years ago

Entertainment8 years agoMod turns ‘Counter-Strike’ into a ‘Tekken’ clone with fighting chickens

-

Politics8 years ago

Politics8 years agoCongress rolls out ‘Better Deal,’ new economic agenda

-

Entertainment8 years ago

Entertainment8 years agoNew Season 8 Walking Dead trailer flashes forward in time

-

Tech8 years ago

Tech8 years agoMicrosoft Paint is finally dead, and the world Is a better place

-

Tech8 years ago

Tech8 years agoHulu hires Google marketing veteran Kelly Campbell as CMO

-

Tech8 years ago

Tech8 years agoFord’s 2018 Mustang GT can do 0-to-60 mph in under 4 seconds

-

Politics8 years ago

Politics8 years agoIllinois’ financial crisis could bring the state to a halt