It’s Smoot-Hawley all over again! At least by this reporter’s calculations, the sweeping tariff regime that President Trump unveiled following the market close on April 2 literally lifts America’s duties on imports to roughly the same level that the much-reviled legislation took them to at the start of the Great Depression.

The ultraprotectionist Smoot-Hawley Act is widely blamed for deepening and prolonging the worst chapter in U.S. economic history. In a 1993 debate with independent presidential candidate Ross Perot on Larry King Live, then VP and free-trade advocate Al Gore brought an antique picture of the two senators, mocking them for a disastrous policy prescription that “sounded reasonable at the time.” Indeed, for the general public and a wide swath of trade experts, going the Smoot-Hawley route is the economic equivalent of shooting yourself in the foot.

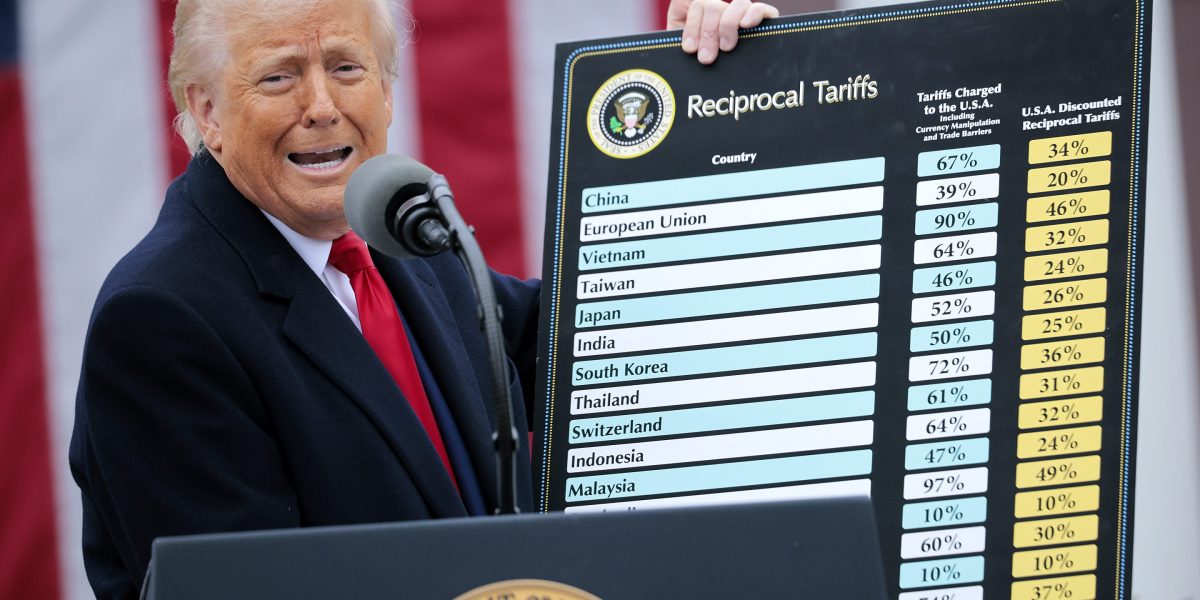

The Trump announcement contained two big surprises. The first: The tariffs are much higher and more extensive than investors and businesses had expected, based on the President’s ever-changing, and at times relatively dovish, musings in the previous days and weeks. Second, the “retaliatory” tariffs were generally gigantic and bore no relation to the posted numerical duties the targeted nations impose on the U.S. For example, the EU slaps an average rate of 2.7% on our goods, according to the World Trade Organization. Yet Trump is piling across-the-board tariffs of 20% on the 27-nation bloc.

What explains the gap? The President reckons that the Community is really charging our exporters 39% via indirect trade barriers that encompass such roadblocks as quotas, technical standards, government procurement policies, and currency manipulation. That the President is imposing a penalty that’s 19 points lower than what the EU’s supposedly charging the U.S. may explain Trump’s claim that he’s being unnecessarily “kind” to our trading partners.

The just-released 2025 Trade Estimate Report on Foreign Trade Barriers compiled by the Office of the U.S. Trade Representative details these alleged restrictions for numerous countries. The administration, however, hasn’t disclosed how it arrived at the precise weight of all indirect barriers, which reach 52% for India and 67% for China, many multiples of the actual rupee or yuan tariffs they collect. It’s the administration’s partner by partner estimate of towering non-tariff walls that mostly explain why the announced rates are so shockingly high.

The key number is the average tariff Trump’s charging across all U.S. imports, and it’s big

Think tanks and Wall Street analysts are rushing to determine the average overall rate, and hence the total dollar charge, that the plan will slap on our imports. That’s also the number American consumers will pay in what amounts to higher taxes if indeed importers pass all the charges along in higher prices, precisely what happened when Trump heaped big duties on the likes of steel and aluminum in his first term. So, this writer calculated those numbers based on the percentage tariff for each nation and the EU, and the dollars in exports they sent Stateside in 2025. It proved perhaps my most head-spinning numerical exercise in several decades as a business reporter.

Trump hit all of the 12 largest exporters to the US with tariffs of at least 20%. China took the hardest punch at 54%, followed by Vietnam (46%), Thailand (36%), Taiwan (32%), Switzerland (31%), India (26%), Japan (24%), Mexico and Canada (25% each), South Korea (25%), Malaysia (24%), and the EU (20%). Fourteenth-ranked Indonesia got dinged 32%. Most of the other 150-plus nations on the list fall under the 10% “universal” tariff regime, including Singapore and Brazil, which sit in 13th and 14th place respectively in export volumes to the U.S.

The 13 heavily penalized supposed bad actors among the 15 largest exporters accounted for $2.92 trillion of foreign goods sold in the America last year. That’s over 70% of $4.11 trillion total. By my calculations, that group alone, based on last year’s numbers, would now be facing around $814 billion in annual duties, or an average rate of 28%. The remaining nations are generally subject to 10% duties on the $1.2 billion remainder, or $120 million. So, all in all, the new tariff bill would mushroom to around $932 billion (the $814 billion for the biggest exporters plus $120 billion for the generally smaller nations at 10%). That’s an average import duty of 22.7%.

How the Trump tariffs compare to Smoot-Hawley

In June of 1930, just eight months after the historic stock market crash that marked the start of the Great Depression, Congress enacted the Smoot-Hawley tariff law, championed by Senator Reed Smoot (R-Utah) and Representative Willis Hawley (R-Ore.). The nation had already turned toward protectionism, chiefly to protect farmers and industrial workers, eight years earlier when the Fordney-McCumber bill raised tariffs substantially, from the single digits to an average of 13.5%, where they stayed pre-Smoot-Hawley. The new law, designed to double down on shielding agricultural workers and folks toiling in the likes of steel and auto plants, raised imposed duties to over 50% on many products. Still, around two-thirds of U.S. imports remained tariff-free, so the average rate rose much less, by 6.3 points to just under 20%.

That’s slightly below the 22% or 23% I get for the Trump plan. And that’s stunning in itself. But the most astounding takeaway is that the Trump blueprint would raise today’s tariffs from the current 3% by nearly 20 points, or sevenfold! That’s three times the jump under Smoot-Hawley.

In the three years following the enactment of Smoot-Hawley, U.S. imports dropped by two-thirds, and, pounded by stiff retaliation from nations such as Germany, the U.K., and Canada, our sales abroad fell by a like percentage. According to most economists, the Trump tariffs are likely to unleash a sharp decline in both what we buy from foreigners and what our producers sell abroad in the years to come, and if the shrinkage in our global trading activity proves even a fraction of the disastrous collapse post-Smoot-Hawley, it’s bad news. The nonpartisan Tax Foundation, in estimates posted before the Trump announcement on April 2, reckoned that the new duties would curb GDP growth by 0.4% a year in the long term. That shaves around a quarter from the 2% or less expansion the CBO projects in the years ahead. And that forecast was based on the new tariffs hitting around half of the $4 trillion Trump targeted. Put simply, Trump rocked America by targeting everything big, meaning at least 10%, and most exports super-big.

Not all distinguished experts believe that Smoot-Hawley triggered the Great Depression. Nobel laureate Milton Friedman ascribed the collapse in the 1930s to overrestrictive monetary policy, and viewed Smoot-Hawley as only a minor factor. But a tariff increase that’s multiple of the one that almost a century ago, was advertised as a path to prosperity, and that at the very least proved a negative, isn’t encouraging. The Smoot-Hawley saga has an interesting coda involving the bill’s cosponsors: In the 1932 election, Hawley lost his primary; Smoot got waxed in the general election; and the Republicans shed 11 seats in one of the worst routs in the annals of senatorial elections.

So far, the markets hate the Trump plan. We’ll soon see if the voters follow suit.

This story was originally featured on Fortune.com

Source link

Entertainment8 years ago

Entertainment8 years ago

Politics8 years ago

Politics8 years ago

Entertainment8 years ago

Entertainment8 years ago

Entertainment8 years ago

Entertainment8 years ago

Tech8 years ago

Tech8 years ago

Tech8 years ago

Tech8 years ago

Tech8 years ago

Tech8 years ago

Politics8 years ago

Politics8 years ago