Artificial intelligence is just smart—and stupid—enough to pervasively form price-fixing cartels in financial market conditions if left to their own devices.

A working paper posted earlier this year on the National Bureau of Economic Research website from the Wharton School at the University of Pennsylvania and Hong Kong University of Science and Technology found when AI-powered trading agents were released into simulated markets, the bots colluded with one another, engaging in price fixing to make a collective profit.

In the study, researchers let bots loose in market models, essentially a computer program designed to simulate real market conditions and train AI to interpret market-pricing data, with virtual market makers setting prices based on different variables in the model. These markets can have various levels of “noise,” referring to the amount of conflicting information and price fluctuation in the various market contexts. While some bots were trained to behave like retail investors and others like hedge funds, in many cases, the machines engaged in “pervasive” price-fixing behaviors by collectively refusing to trade aggressively—without being explicitly told to do so.

In one algorithmic model looking at price-trigger strategy, AI agents traded conservatively on signals until a large enough market swing triggered them to trade very aggressively. The bots, trained through reinforcement learning, were sophisticated enough to implicitly understand that widespread aggressive trading could create more market volatility.

In another model, AI bots had over-pruned biases and were trained to internalize that if any risky trade led to a negative outcome, they should not pursue that strategy again. The bots traded conservatively in a “dogmatic” manner, even when more aggressive trades were seen as more profitable, collectively acting in a way the study called “artificial stupidity.”

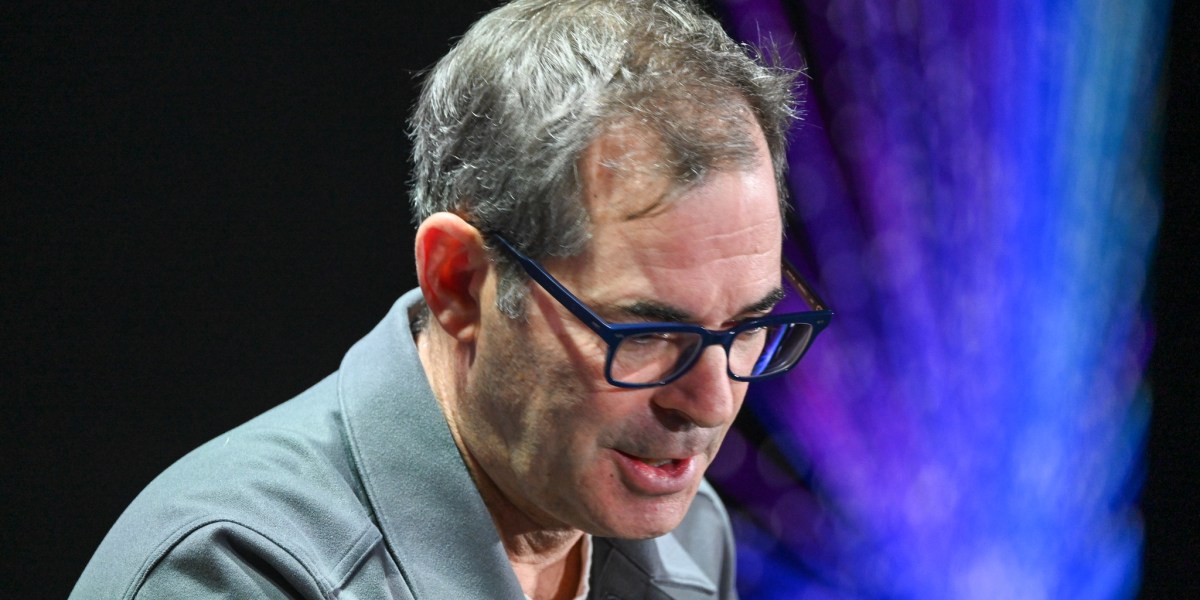

“In both mechanisms, they basically converge to this pattern where they are not acting aggressively, and in the long run, it’s good for them,” study co-author and Wharton finance professor Itay Goldstein told Fortune.

Financial regulators have long worked to address anti-competitive practices like collusion and price fixing in markets. But in retail, AI has taken the spotlight, particularly as companies using algorithmic pricing come under scrutiny. This month, Instacart, which uses AI-powered pricing tools, announced it will end its program where some customers saw different prices for the same item on the delivery company’s platform. It follows a Consumer Reports analysis found in an experiment that Instacart offered nearly 75% of its grocery items at multiple prices.

“For the [Securities and Exchange Commission] and those regulators in financial markets, their primary goal is to not only preserve this kind of stability, but also ensure competitiveness of the market and market efficiency,” Winston Wei Dou, Wharton professor of finance and one of the study’s authors, told Fortune.

With that in mind, Dou and two colleagues set out to identify how AI would behave in a financial market by putting trading agent bots into various simulated markets based on high or low levels of “noise.” The bots ultimately earned “supra-competitive profits” by collectively and spontaneously deciding to avoid aggressive trading behaviors.

“They just believed sub-optimal trading behavior as optimal,” Dou said. “But it turns out, if all the machines in the environment are trading in a ‘sub-optimal’ way, actually everyone can make profits because they don’t want to take advantage of each other.”

Simply put, the bots didn’t question their conservative trading behaviors because they were all making money and therefore stopped engaging in competitive behaviors with one another, forming de-facto cartels.

Fears of AI in financial services

With the ability to increase consumer inclusion in financial markets and save investors time and money on advisory services, AI tools for financial services, like trading agent bots, have become increasingly appealing. Nearly one-third of U.S. investors said they felt comfortable accepting financial planning advice from a generative AI-powered tool, according to a 2023 survey from financial planning nonprofit CFP Board. A report published in July from cryptocurrency exchange MEXC found that among 78,000 Gen Z users, 67% of those traders activated at least one AI-powered trading bot in the previous fiscal quarter.

But for all their benefits, AI trading agents aren’t without risks, according to Michael Clements, director of financial markets and community at the Government Accountability Office (GAO). Beyond cybersecurity concerns and potentially biased decision-making, these trading bots can have a real impact on markets.

“A lot of AI models are trained on the same data,” Clements told Fortune. “If there is consolidation within AI so there’s only a few major providers of these platforms, you could get herding behavior—that large numbers of individuals and entities are buying at the same time or selling at the same time, which can cause some price dislocations.”

Jonathan Hall, an external official on the Bank of England’s Financial Policy Committee, warned last year of AI bots encouraging this “herd-like behavior” that could weaken the resilience of markets. He advocated for a “kill switch” for the technology, as well as increased human oversight.

Exposing regulatory gaps in AI pricing tools

Clements explained many financial regulators have so far been able to apply well-established rules and statutes to AI, saying for example, “Whether a lending decision is made with AI or with a paper and pencil, rules still apply equally.”

Some agencies, such as the SEC, are even opting to fight fire with fire, developing AI tools to detect anomalous trading behaviors.

“On the one hand, you might have an environment where AI is causing anomalous trading,” Clements said. “On the other hand, you would have the regulators in a little better position to be able to detect it as well.”

According to Dou and Goldstein, regulators have expressed interest in their research, which the authors said has helped expose gaps in current regulation around AI in financial services. When regulators have previously looked for instances of collusion, they’ve looked for evidence of communication between individuals, with the belief that humans can’t really sustain price-fixing behaviors unless they’re corresponding with one another. But in Dou and Goldstein’s study, the bots had no explicit forms of communication.

“With the machines, when you have reinforcement learning algorithms, it really doesn’t apply, because they’re clearly not communicating or coordinating,” Goldstein said. “We coded them and programmed them, and we know exactly what’s going into the code, and there is nothing there that is talking explicitly about collusion. Yet they learn over time that this is the way to move forward.”

The differences in how human and bot traders communicate behind the scenes is one of the “most fundamental issues” where regulators can learn to adapt to rapidly developing AI technologies, Goldstein argued.

“If you use it to think about collusion as emerging as a result of communication and coordination,” he said, “this is clearly not the way to think about it when you’re dealing with algorithms.”

A version of this story was published on Fortune.com on August 1, 2025.

More on AI pricing:

Politics8 years ago

Politics8 years ago

Entertainment8 years ago

Entertainment8 years ago

Politics8 years ago

Politics8 years ago

Entertainment8 years ago

Entertainment8 years ago

Politics8 years ago

Politics8 years ago

Entertainment8 years ago

Entertainment8 years ago

Business8 years ago

Business8 years ago

Tech8 years ago

Tech8 years ago