Business

Tim Wu knows where you got your ‘economic resentment’ and that ‘weird feeling of something you like getting worse’: It’s ‘the age of extraction’

Published

2 months agoon

By

Jace Porter

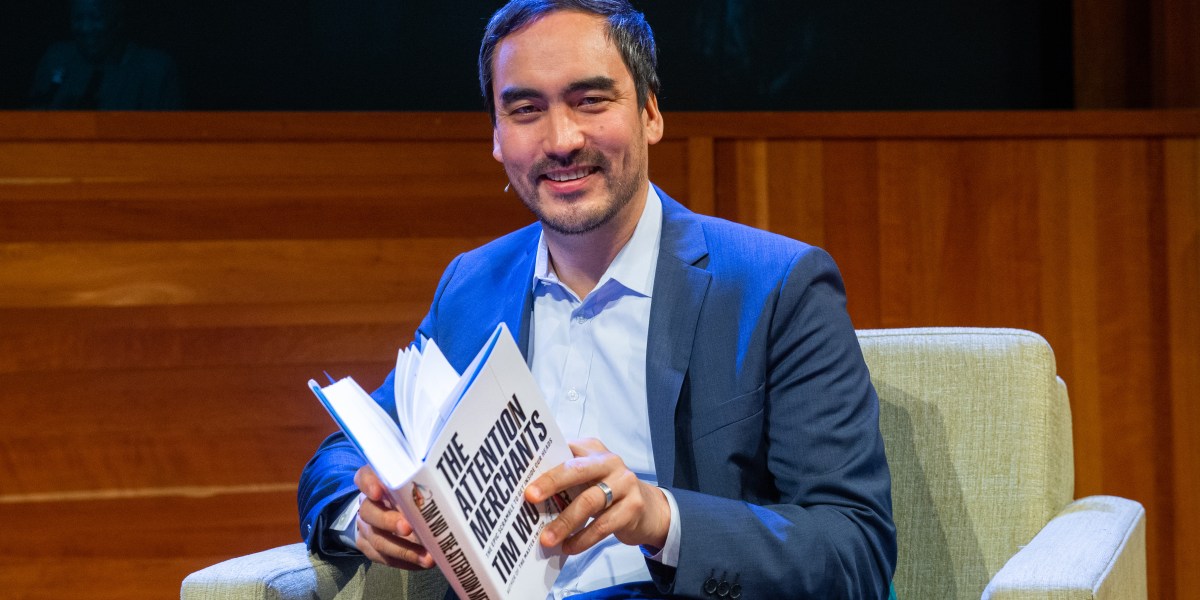

Tim Wu, the influential Columbia Law School professor who previously served in the Biden administration, is back with a message: Modern American capitalism has devolved into a system defined by the accumulation of market power and “extraction,” generating a profound sense of “economic resentment” across the nation.

Speaking to Fortune upon the release of his newest book, The Age of Extraction, Wu connected the current political volatility to a widespread feeling that “our system is not fair.” He suggests this pervasive anger stems from individuals feeling “out-powered, as opposed to out-competed,” which creates far more resentment than losing in a fair fight.

Wu defines the core problem as a shift in business goals: moving away from building “a good product that people want to buy because it’s good,” toward models seeking to “find power over someone and suck as much as you can out of them.” Wu agreed his take has many similarities to recent writings from his old friend, Cory Doctorow; even though Doctorow’s argument is mainly about tech, he acknowledged they share much of the same DNA. “I think that that is kind of an economy-wide problem. Everything kind of just creeps. It’s that weird feeling of something you like becoming worse.”

Chalking it up to a “lack of discipline,” Wu said too many companies let things drift in the modern age of extraction. Strong competitors, legal enforcement, and a company’s employees can all stress a sense of discipline, he said, “but none of those are very strong right now in so many markets …a lack of discipline lets firms get away with making their products and services worse.” Zooming out a bit further, this trend challenges the fundamental idea of American progress, especially in the tech industry, which is supposed to be the “invention industry” constantly driving improvement.

“My understanding of America is that it’s the place where things are supposed to get better,” Wu said. Living in an age when so many things are getting worse instead “cuts at the core of the idea of America, but also the tech industry [idea] of progress,” he argued—but he does see an unlikely solution.

As a sports fan, Wu said there’s a clear example of a market structure that has discipline, where things are not in fact getting worse, where things are not extracted. It’s a good product that people want to buy because it’s good: the National Football League. He said the NFL illustrates the importance of fair rules, with “aggressive rebalancing,” achieved through mechanisms such as the market cap, the draft, and adjusted schedules.

How the NFL could fix the economy

While the NFL is still competitive and meritocratic, it ensures that even the worst team “has some chance to get a great quarterback” and become competitive again, like the Kansas City Chiefs, who have enjoyed historic success with their franchise players Patrick Mahomes and Travis Kelce. Teams from smaller markets like Kansas City routinely dominating those from larger markets, like New York, would be unthinkable in “just an economic game,” Wu argued. In contrast, Wu points to Major League Baseball, which has been “distorted by out of control spending.” This results in an “absurd” mismatch of resources, where smaller teams are crippled by resource deficits, rather than poor play. (The big-market Los Angeles Dodgers, with the biggest payroll in baseball history, just celebrated their second-straight World Series win.)

The NFL’s success serves as a model for how the U.S. economy should function. “I’m not a socialist,” Wu told Fortune. “In some ways, I’m here to try to not destroy capitalism, but return it to what it can be.” In his new book, Wu writes about the “extractors” and the “extracted” in language that sounds similar to the K-shaped economy dominating headlines in 2025, a shorthand for an economy where the rich get richer and the poor get poorer. “I think it is closely linked,” Wu said, adding it wasn’t his intention to directly link them in his book.

“I think we have moved in the direction of an economy where the focus of business models is the accumulation of market power and then extraction, which, by definition, almost by basic microeconomics is going to result in a lot of [upward] wealth redistribution.” Wu added that he thinks many of the industries that used to provide a middle class or even upper middle class lifestyle “are being driven down in favor of a couple industries that have outsized returns,” including concentrated middlemen, certain parts of finance, and tech platforms.

If Americans love the NFL so much on their TV every Sunday, he argued, why not apply the same principles from the league to how we structure our society? After all, Wu points out, he’s been right about some things before, to society’s benefit.

Net neutrality and attention

A distinguished professor at Columbia University who The New York Times described as “an architect of Biden’s antitrust policy,” Wu has not one but several big ideas to his credit. One is “net neutrality,” the concept authored by Wu over 20 years ago that internet service providers must be agnostic about what content flows through them. This was a clear victory, as the law is still on the books. Another is about “the attention economy,” a thesis and book (The Attention Merchants) that Wu released roughly 10 years ago, sounding the alarm on how attention was turning into a commodity in the internet age and was increasingly exploited.

Wu said he wants to be humble, but genuinely believes he was right about the attention economy a decade ago. “Maybe it was sort of obvious,” he said, but the resource of human attention becoming scarcer and more valuable and “companies are very sophisticated at essentially harvesting this resource from us at a very low price.”

As a parent (his kids are 9 and 12), Wu said he notices “people are much more sensitive” about their children using attention-economy products and believes there has been a counter-movement to reclaim attention. He notes large language models are becoming popular in a very similar way and there’s no advertising on them for now, so “it’s not like the problem has gone away and it’s not as if we are able to get away from our phones. I just think it’s better recognized.”

A dance with politics and the ‘beer wars’

In his conversation with Fortune, Wu reflected on his time in the Biden White House, saying it was “an important and great experience,” but he wishes they were able to do more on children’s privacy issues as he believes 99% of Americans would support legislation in this area. Yet, it was “impossible to get a vote on anything, any issue” when he worked in the White House. Congress “doesn’t want to let things get to a vote,” he said, attributing much of the gridlock to the fact that “influence of big tech over politics has just gotten so strong.”

When asked if he has any interest in working in government again, perhaps along his longtime friend Lina Khan in Zohran Mamdani’s mayoralty in New York, Wu only said he’s “very supportive of the new mayor.” He said he could get involved in politics in some fashion again, but is “much more in a family mode” these days. Wu has a perhaps surprisingly long history in public service, having worked in antitrust enforcement at the Federal Trade Commission as well as working on competition policy for the National Economic Council during the Obama administration. In 2014, Wu was a Democratic primary candidate for lieutenant governor of New York, where he first met Khan.

Wu did get involved in some intra-left economics squabbles recently, as he took Khan’s side of the debate on plans to reduce the price of hot dogs and beers at New York City sports stadiums. The “beer wars” erupted on Twitter, with Wu and Khan on the side in favor of cutting prices, and Matt Yglesias and Jason Furman on the more centrist side, arguing for letting the free market set prices. Wu said it was a “strange battle” and said there seems to be a tension on the left around economics that he doesn’t fully understand, adding that he has worked productively alongside Furman in the past. In general, he said he thinks “our politics is very angry, partially because of economic resentment … it gets expressed in strange ways and goes in all kinds of directions.” Tying it back to his new book, he believes that in general, “we let things go a little too far” and we “just kind of lost touch with the tradition of broad-based wealth that was the American way.”

When asked about the uproar among the New York business community about Mamdani and the term “democratic socialism,” Wu said it has become a bit of an “umbrella” term, because “a real socialist believes that all the means of production should be owned by the state” and Mamdani’s democratic socialists aren’t exactly advocating that. He said maybe some on the left would like more direct ownership of public things, but it’s more a mixture of that same “we’ve gone too far” feeling. Wu added that he personally feels most affiliated with Louis Brandeis, a judicial figure from the Progressive Movement who was influential in developing modern antitrust law and the “right to privacy” concept.

“If you want to talk about America drifting towards something more like Communism, it is more in this idea of real, very active state involvement” that you see in the Trump administration, which has, for instance, taken stakes in major U.S. companies such as Intel. “That’s actually more like socialism” and what you see in a “command economy,” Wu said. He compared it to Stalinism or fascism under Mussolini, “neither of which are the most flattering labels, I realize.” It’s also, of course, similar to Chinese Communism, Wu said.

Wu said he hopes this doesn’t come to pass. There could be an America where the idea of doing business is extraction—trying to find power over someone and sucking out as much as possible—and another, better way. “I think we can do better. I’m a big believer, frankly, in business. I think we need a return to like this idea you can reap what you sow, that your investments will get you somewhere.”

You may like

Business

Stock market today: Dow futures tumble 400 points on Trump’s tariffs over Greenland, Nobel prize

Published

5 hours agoon

January 19, 2026By

Jace Porter

U.S. stock futures dropped late Monday after global equities sold off as President Donald Trump launches a trade war against NATO allies over his Greenland ambitions.

Futures tied to the Dow Jones industrial average sank 401 points, or 0.81%. S&P 500 futures were down 0.91%, and Nasdaq futures sank 1.13%.

Markets in the U.S. were closed in observance of the Martin Luther King Jr. Day holiday. Earlier, the dollar dropped as the safe haven status of U.S. assets was in doubt, while stocks in Europe and Asia largely retreated.

On Saturday, Trump said Denmark, Norway, Sweden, France, Germany, the United Kingdom, the Netherlands, and Finland will be hit with a 10% tariff starting on Feb. 1 that will rise to 25% on June 1, until a “Deal is reached for the Complete and Total purchase of Greenland.”

The announcement came after those countries sent troops to Greenland last week, ostensibly for training purposes, at the request of Denmark. But late Sunday, a message from Trump to European officials emerged that linked his insistence on taking over Greenland to his failure to be award the Nobel Peace Prize.

The geopolitical impact of Trump’s new tariffs against Europe could jeopardize the trans-Atlantic alliance and threaten Ukraine’s defense against Russia.

But Wall Street analysts were more optimistic on the near-term risk to financial markets, seeing Trump’s move as a negotiating tactic meant to extract concessions.

Michael Brown, senior research strategist at Pepperstone, described the gambit as “escalate to de-escalate” and pointed out that the timing of his tariff announcement ahead of his appearance at the Davos World Economic Forum this week is likely not a coincidence.

“I’ll leave others to question the merits of that approach, and potential longer-run geopolitical fallout from it, but for markets such a scenario likely means some near-term choppiness as headline noise becomes deafening, before a relief rally in due course when another ‘TACO’ moment arrives,” he said in a note on Monday, referring to the “Trump always chickens out” trade.

Similarly, Jonas Goltermann, deputy chief markets economist at Capital Economics, also said “cooler heads will prevail” and downplayed the odds that markets are headed for a repeat of last year’s tariff chaos.

In a note Monday, he said investors have learned to be skeptical about all of Trump’s threats, adding that the U.S. economy remains healthy and markets retain key risk buffers.

“Given their deep economic and financial ties, both the US and Europe have the ability to impose significant pain on each other, but only at great cost to themselves,” Goltermann added. “As such, the more likely outcome, in our view, is that both sides recognize that a major escalation would be a lose-lose proposition, and that compromise eventually prevails. That would be in line with the pattern around most previous Trump-driven diplomatic dramas.”

Business

Goldman investment banking co-head Kim Posnett on the year ahead, from an IPO ‘mega-cycle’ to another big year for M&A to AI’s ‘horizontal disruption’

Published

8 hours agoon

January 19, 2026By

Jace Porter

Ahead of the World Economic Forum‘s Annual Meeting in Davos, Switzerland, Fortune connected with Goldman Sachs’ global co-head of investment banking, Kim Posnett, for her outlook on the most urgent issues in business as 2026 gathers steam.

A Fortune Most Powerful Woman, Posnett is one of the bank’s top dealmakers, also serving as vice chair of the Firmwide Client Franchise Committee and is a member of the Management Committee. She was previously the global head of the Technology, Media and Telecommunications, among several other executive roles, including Head of Investment Banking Services and OneGS. She talked to Fortune about how she sees the current business environment and the most significant developments in 2026, in terms of AI, the IPO market and M&A activity. Goldman has been the No. 1 M&A advisory globally for the last 20 years, including in 2025 — and Posnett has been one of the star contributors, advising companies including Amazon, Uber, eBay, Etsy, and X.

- Heading into Davos, how would you describe the current environment?

As the global business community converges at Davos, we are seeing powerful catalysts driving M&A and capital markets activity. The foundational drivers that accelerated business activity in the second half of 2025 have continued to improve and remain strong heading into 2026. A constructive macro backdrop — including AI serving as a growth catalyst across sectors and geographies — is fueling CEO and board confidence, and our clients are looking to drive strategic and financing activity focused on scale, growth and innovation. As AI moves from theoretical catalyst to an industrial driver, it is creating a new set of priorities for the boardroom that are top of mind for every client we serve heading into 2026.

- What were the most significant AI developments in 2025, and what should we expect in 2026?

2025 was a breakout year for AI where we exited the era of AI experimentation and entered the era of AI industrialization. We witnessed major technical and structural breakthroughs across models, agents, infrastructure and governance. It was only a year ago, in January 2025, when DeepSeek launched its DeepSeek-R1 reasoning model challenging the “moats” of closed-source models by proving that world-class reasoning could be achieved with fully open-source models and radical cost efficiency. That same month, Stargate – a historic $500 billion public-private joint venture including OpenAI, SoftBank and Oracle – signaled the start of the “gigawatt era” of AI infrastructure. Just two months later in March 2025, xAI’s acquisition of X signaled a new strategy where social platforms could function as massive real-time data engines for model training. By year end, we saw massive, near-simultaneous escalation in model capabilities with the launches of OpenAI’s GPT-5.1 Pro, Google’s Gemini 3, and Anthropic’s Claude 4.5, all improving deep thinking and reasoning, pushing the boundaries of multimodality, and setting the standard for autonomous agentic workflows.

In the enterprise, the conversation has matured from “What is AI?” just a few years ago to “How fast can we deploy?” We have moved past the pilot phase into a period of deep structural transformation. For companies around the world, AI is fundamentally reshaping how work gets done. AI is no longer just a feature; it is the foundation of a new kind of productivity and operating leverage. Forward-leaning companies are no longer just using AI for automation; they are building agentic workflows that act as a force multiplier for their most valuable asset: human capital. We are starting to see the first real, measurable returns on investment as firms move from ‘AI-assisted’ tasks to ‘AI-led’ processes, fundamentally shifting the cost and speed of execution across organizations.

Of course, all this progress is not without regulatory and policy complexities. As AI reaches consumer, enterprise and sovereign scale, we are seeing a divergence in global policy that boards must navigate with care. In the United States, recent Executive Orders — such as the January 2025 ‘Removing Barriers’ order and the subsequent ‘Genesis Mission’ — have signaled a decisive shift toward prioritizing American AI dominance by rolling back prior reporting requirements and accelerating infrastructure buildouts. Contrast this with the European Union, where the EU AI Act is now in full effect, imposing strict guardrails on ‘high-risk’ systems and general-purpose models. Meanwhile, the UK has adopted a “pro-innovation” hybrid model: on the one hand, promoting “safety as a service”, while also investing billions into national compute and ‘AI Growth Zones’ to bridge the gap between innovation and public trust. For our clients, the challenge is no longer just regulatory compliance; it is strategic planning and arbitrage – deciding where to build, where to deploy, who to partner with, what to buy and how to maintain a global edge across a fragmented regulatory landscape.

As we enter 2026, the pace of innovation isn’t just accelerating; it is forcing a total rethink of business processes and capital allocation for every global enterprise.

- Given the expectation and anticipation for IPOs this year, what is your outlook for the market and how will it be characterized?

We are entering an IPO “mega-cycle” that we expect will be defined by unprecedented deal volume and IPO sizes. Unlike the dot-com wave of the late 1990s, which saw hundreds of small-cap listings, or even the 2020-2021 surge driven by a significant number of billion-dollar IPOs, this next IPO cycle will have greater volume and the largest deals the market has ever seen. It will be characterized by the public debut of institutionally mature titans, as well as totally disruptive, fast moving and capital consumptive innovators. Over the last decade, some companies have stayed private longer and raised unprecedented amounts of private capital, allowing a cohort of businesses to reach valuations and operational scale previously unseen in the private markets. We are no longer talking about “unicorns” — we are talking about global companies with the gravity and scale of Fortune 500 incumbents at the time they go public. For investors, the reopening of the IPO window will enable an opportunity to invest in the most transformative and fastest growing companies in the world and a generational re-weighting of the public indices.

In 2018, the five largest public tech companies were collectively valued at $3.3 trillion, led by Apple at ~$1 trillion. Today, the five largest public tech companies are valued at $18.3 trillion, more than five and half times larger. Even more significant, the 10 largest private tech companies in 2018 were valued at $300 billion. Today, the 10 largest private tech companies are valued at $3 trillion, more than 10 times larger. These are iconic, generational companies with unprecedented private market caps some of which have unprecedented capital needs which should lead to an unprecedented IPO market.

Each of these companies will have their own objectives on IPO timing, size and structure which will influence if, how and when they come to the market, but the potential across the board is significant. During the last IPO wave, Goldman Sachs was at the center of IPO innovation by leading the first direct listings and auction IPOs, and we expect more innovation with this upcoming wave. The current confluence of a constructive macro backdrop and groundbreaking technological advancements is doing more than just reopening the window; it is creating a generational opportunity for investors to participate in the companies that will define the next century of global business.

- M&A activity exploded in 2025, are the markers there for another boom year?

As we enter 2026, the global M&A market has transitioned from a year of recovery ($5.1 trillion of M&A volume in 2025, up 44% YoY) to one that is bold and strategic. While the second half of 2025 was defined by a “thawing” — driven by a constructive regulatory environment, fed easing cycle and normalizing valuations — the year ahead will be defined by ambition.

We have entered an era of broad, bold and ambitious strategic dealmaking: transformative, high-conviction transactions where industry leaders are no longer just consolidating for scale, but also moving aggressively to acquire the strategic assets, AI capabilities and digital infrastructure that will define the next decade. CEO and board confidence have reached a multi-year high, underpinned by the realization that in an AI-industrialized economy, standing still is the greatest risk of all. The quality and pace of strategic discussions that we are having with our clients signals that the world’s most influential companies — across sectors and regions — are ready to deploy their balance sheets and public currencies to redraw the competitive map.

AI is no longer an isolated tech trend; it is a horizontal disrupter, broadening the appetite for strategic M&A across every sector of the economy. While the dialogue in boardrooms has moved from theoretical ‘AI pilots’ to large-scale capital deployment, the speed of technology is currently outpacing traditional governance frameworks. Boards and management teams are being asked to make multi-billion dollar, high-stakes decisions in a landscape where historical benchmarks often no longer apply. In this environment, M&A has become a tool for strategic leapfrogging — allowing companies to move both defensively to protect their core and offensively to secure the critical infrastructure and talent needed for non-linear growth. Success in 2026 will be defined by strategic conviction: the ability to turn this unprecedented complexity into a clear, actionable strategy and competitive advantage.

As AI continues to reshape corporate M&A strategy, we are also seeing financial sponsors return to the center of the M&A stage. Sponsor M&A activity accelerated sharply in 2025 — with M&A volumes surging over 50% as the bid-ask spread between buyers and sellers started to narrow, financing markets became more constructive and innovative deal structures enabled private equity firms to pursue larger, more complex transactions. With $1 trillion of global sponsor dry powder and over $4 trillion of unmonetized sponsor portfolio companies, the pressure for capital return to LPs has continued to escalate. Financial sponsors are entering 2026 with a dual-focus: executing take-privates and strategic carveouts to deploy fresh capital, while simultaneously utilizing reopened monetization paths – from IPOs to secondary sales to strategic sales — to satisfy demand for liquidity. With monetization paths reopening and valuation gaps narrowing, sponsors are entering 2026 with greater flexibility, reinforced by a healthier macroeconomic backdrop and improving liquidity conditions.

This Q&A is based on an email conversation with Kim Posnett. This piece has been edited for length and clarity.

Business

Half of veterans leave their first post-military jobs in less than a year—This CEO aims to fix that

Published

8 hours agoon

January 19, 2026By

Jace Porter

Taking a career leap can be daunting, but all professionals inevitably have to face the music; most will change jobs or industries at some point, whether they want to or not. But for U.S. veterans exiting service and heading into civilian life, the transition has been especially difficult—and it’s an issue that’s intensifying their unemployment. That’s why financial services titan USAA is putting its money where its mouth is with a $500 million initiative to get members back on their feet.

“What we created here since I took over as CEO is a completely revamped way of hiring our veterans and military spouses,” the company’s CEO, Juan C. Andrade, tells Fortune. “This is not just for the benefit of USAA—this is for the benefit of the military community.”

USAA launched its “Honor Through Action” program in 2025, committing half a billion dollars over the next five years to improve the careers, financial security, and well-being of its customers—many of whom are active military, veterans, or related to them. It’s the brainchild of Andrade, who stepped into the company’s top role in April last year. As someone who also left a longstanding career in the federal government, he understands the growing pains that come with an intimidating career pivot. And for thousands of USAA members, the situation is dire.

Around half of veterans ditch their initial post-military jobs within the first year, according to the Department of Defense’s Transition Assistance Program, and USAA’s CEO believes a lack of thoughtful transition services is largely to blame. When colonels, generals, and sergeants leave behind their high-powered jobs, Andrade says some struggle to adapt both emotionally and skills-wise.

While businesses are required to re-employ former employees who return from military duty per U.S. federal law, those stepping into civilian roles for the first time often need a helping hand. And even before they exit the military, the careers of their partners tend to suffer.

The jobless rate of military spouses has hovered around 22% over the past decade, according to Hiring Our Heroes. That’s more than four times higher than the 4.6% nationwide unemployment rate. When their partners need to relocate for a new duty assignment, spouses are 136% more likely to be unemployed within six months, according to a 2024 Defense Department survey.

This trend of low job retention among veterans and spouse joblessness can be detrimental to the financial and professional livelihoods of American military families. So Andrade is leading the charge to get them on payroll. Corporations like JPMorgan have ramped up ex-military resources, and services like Armed Forces YMCA have long been assisting veterans; But USAA’s CEO says the issue needs a more targeted approach.

“While there’s a lot of organizations that are very well-meaning and do some very good work, the approach has been fragmented,” Andrade explains. “The problem with private sector companies is [if they] have not had that experience of service, or if they don’t have a large population of employees that serve, it’s very difficult to understand the fact that they’ve lost their tribe. The fact that, in a lot of ways, they’ve lost their sense of belonging to something greater than self.”

USAA’s $500 million plan and new fellowship pathways

USAA already has several veteran employment initiatives on the docket this year. This March, the company tells Fortune it will host a nationwide U.S. Chamber of Commerce Foundation program, Hiring our Heroes, in San Antonio to connect on the issue. And in the coming months, USAA will host events with nonprofit and HR association SHRM to brainstorm the best ways to improve military hiring in the U.S.

In stride with Honor Through Action, USAA also launched two 18-month fellowship programs designed to transition military personnel into full-time company positions: Summit and Signal. In three six-month rotations, participants cycle through different parts of the financial services giant to find the best fit. The future leadership track, Summit, rotates fellows through departments including business strategy, operational planning, and product ownership. Starting anew can be isolating, so USAA is ensuring that military personnel are not walking these career paths alone—veterans are connected to mentors every step of the way.

“Those 18 months are incredibly important, because it goes to show you: What is it that you can do? How does a private company actually work? What is it that you do on a daily basis?” Andrade says. “They get one-on-one mentorship and support every step of the way with people that have already walked in their shoes and been successful, so all of that helps.”

And just like what other companies are looking for in white-collar talent, USAA places a special emphasis on AI-savvy workers. That’s where the Signal fellowship comes into play: the pathway targets applicants with tech know-how, cycling them between assignments including technical solutions and data processing. The CEO notes that the military community is teeming with tech skills, and some already come with prior training from U.S. Cyber Command roles. Aside from getting ex-military members back into work, Signal is also proving to be extremely beneficial for the business itself.

“We’re always looking for people who have the expertise and skill sets in data science or data engineering,” Andrade continues. “As they retire from the Air Force, the Army, the Navy, we bring them into a specialized program focused on their skills and how they can help us from technology experience.”

Serving an overlooked population: veteran spouses struggling with joblessness

Even when they’re not deployed, U.S. military personnel are battling wars at home—depression, financial insecurity, and homelessness. But one group is often ignored in the fight: their spouses. The husbands and wives of military personnel face sky-high unemployment rates and long-term instability due to the nature of their partners’ jobs. But Andrade recognizes them as an overlooked and underutilized pool of professionals.

“Military spouses are an incredible source of talent—they’re literally the CFO and the CEO of their home,” USAA’s CEO says. “When their spouses are deployed, when there’s a permanent change of station for their spouse, they have to leave their job. And if they don’t have that flexibility, then you know that’s why the unemployment rate is so high.”

USAA is funneling its resources to get to the root of the issue; as part of the Honor Through Action initiative, the company tells Fortune it will host Military Spouse Advisory Councils in San Antonio this March. The mission is to help shape policy, programs, and resources to better serve the unique needs of military families. That same month, the business also plans to work with other organizations in funding Blue Star Families’ release of Military Spouse Employment Research with the aim of pinpointing actionable solutions to their raging unemployment. And reflecting internally, Andrade reports that USAA will continue to lead by example.

“We can offer a lot of flexibility… Having that level of empathy and understanding becomes very critical,” he says. “This is where we hope—with Honor Through Action—to be able to help companies understand the value that [military spouses] have, but also why you need to treat them a little bit differently given their personal situation.”

TMZ Comedy Tour Debuts, Brittany Schmitt & Mateen Stewart Host Hollywood Ride

Bloomingdale’s names Russ Patrick GMM of home

Karol G and Boyfriend Feid Break Up After 3 Years

Trending

-

Politics8 years ago

Politics8 years agoCongress rolls out ‘Better Deal,’ new economic agenda

-

Entertainment9 years ago

Entertainment9 years agoNew Season 8 Walking Dead trailer flashes forward in time

-

Politics9 years ago

Politics9 years agoPoll: Virginia governor’s race in dead heat

-

Politics8 years ago

Politics8 years agoIllinois’ financial crisis could bring the state to a halt

-

Entertainment8 years ago

Entertainment8 years agoThe final 6 ‘Game of Thrones’ episodes might feel like a full season

-

Entertainment9 years ago

Entertainment9 years agoMeet Superman’s grandfather in new trailer for Krypton

-

Business9 years ago

Business9 years ago6 Stunning new co-working spaces around the globe

-

Tech8 years ago

Tech8 years agoHulu hires Google marketing veteran Kelly Campbell as CMO