Business

As data-center operator CoreWeave prepares for earnings, stock bears worry its finances are emblematic of an AI bubble

Published

4 weeks agoon

By

Jace Porter

A vast data center in Plano, Texas, is a symbol of the enormous AI infrastructure boom that has boosted stock markets and driven U.S. economic growth over the past year. The data center occupies more than 450,000 square feet and cost $1.6 billion to construct and equip. It supplies 30 megawatts of computing power to train and run AI models. Yet the company that runs it is a leading candidate to be ground-zero for a future AI financial meltdown.

The data center is one of dozens around the world operated by CoreWeave, a company that develops and manages data centers and sells their computing capacity to technology companies. Its business is at the center of the AI economy—providing computing power to meet the voracious demand of the likes of Microsoft and OpenAI. But CoreWeave doesn’t own the Plano facility, nor does it own most of the data hubs it’s operating. And that is a part of the problem.

The company is built, by its own admission, on a mountain of debt—obligations it has piled up as it races to build out a network of server farms for its customers. And that mountain looms far larger than the piles of cash that CoreWeave has brought in the door so far. When the company announces earnings on Monday, bulls and bears alike will be watching to see how its revenue is growing, and whether it has been able to pare its losses. CoreWeave’s earnings are likely to be a bellwether for the state of the entire AI boom, and for the industry’s massive and expensive infrastructure buildout in particular.

CoreWeave has $7.6 billion in current liabilities—bills that fall due within 12 months—on its balance sheet, and $11 billion in debt overall, according to its most recent quarterly earnings report, filed in August. Coming from a tech giant like Google or Microsoft with tens of billions in free cash flow, such numbers wouldn’t raise an eyebrow. But CoreWeave’s revenues were only $1.9 billion in 2024. On its Q2 earnings call, CEO Michael Intrator told analysts that full year 2025 revenue would land between $5.15 billion to $5.35 billion. On the same call, the CEO said he expected CoreWeave’s capex for the year would total between $20 billion and $23 billion.

Those short-term figures pale beside a bigger and potentially more onerous obligation that isn’t on its balance sheet: the $34 billion in scheduled lease payments that will start kicking in between now and 2028. Many of those payments are stretched over relatively long terms, of 10 years or more. Still, some of this is for data centers and office buildings that have not yet begun to operate or bring in revenue—representing a vulnerability if any of the as-yet-unprofitable startups CoreWeave sells computing services to are unable to meet their contractual obligations, or if construction delays mean CoreWeave is not able to provide capacity on time, allowing customers to cancel contracts.

In a sense, Coreweave is a metaphor for the broader AI industry at the present moment, as top companies commit to enormous capex spending today in the confidence that it’ll be justified by future revenue from AI platforms and services. Investors appear to be broadly convinced by the company’s narrative: CoreWeave’s stock price is up 160% since the company’s IPO in March.

But Fortune’s analysis of CoreWeave’s filings with the Securities and Exchange Commission, which are laced with warnings and caveats, show how risky the company’s business model could be. In interviews with several analysts, bulls and bears agreed that CoreWeave’s fundamentals, as reflected in its filings, don’t currently add up. “A lot has to go right,” says Thomas Blakely, a managing director of software equity research at Cantor Fitzgerald, who rates CoreWeave “overweight.” (Of 26 equity analysts who currently cover the stock, 14 had the equivalent of buy or outperform ratings on the shares, while nine had “hold” ratings, and three had “underperform” or “sell” recommendations, according to data from S&P Market Intelligence.)

The bears see CoreWeave as a strong candidate to find itself underwater with its mounting liabilities, making it potentially the first domino to fall in the AI ecosystem. “To say they’ll scale out of this is questionable,” says Gil Luria, the head of technology research at the investment firm D.A. Davidson. “I don’t see how it becomes more profitable.” He believes that the likeliest outcome for CoreWeave on a five-year time horizon is bankruptcy—either because its current customers will be able to rely on their own infrastructure by then, or because an increasingly stretched CoreWeave will no longer be able to borrow.

In a statement to Fortune, a company spokesperson said that “CoreWeave’s capital structure and financial performance are strong and underpinned by long-term take-or-pay contracts signed with the world’s leading enterprises and AI labs who partner with CoreWeave because we deliver the best AI cloud.” The statement went on to say that the company structured its contracts to “support and repay any related debt obligations while generating additional free cash flow. CoreWeave operates in a supply-constrained market where demand far exceeds capacity, and our hyper-growth is evidence of the trust leading companies place in us to power their most critical AI workloads.”

Betting big on tomorrow’s revenue

With the company continuing to make huge new spending commitments even as it books new future revenue, AI investors’ attention will be glued to its upcoming quarterly earnings report. One number that everyone will be watching is CoreWeave’s “remaining performance obligations,” or RPOs—essentially revenues that CoreWeave has booked but that have not yet been paid. (Like its scheduled lease payments, CoreWeave’s RPOs are excluded from its balance sheet.)

If CoreWeave is booking the kinds of contracts that will pull it out of debt sooner rather than later, the RPOs level—and the forecast for how quickly those future bookings are likely to turn into actual cash—are where they would show up. The company has announced several major new deals since its last quarterly earnings announcement, including a $14.2 billion agreement to supply Meta with computing capacity, and an pact with AI startup Poolside for a data center stuffed with 40,000 Nvidia GPUs. So it is likely its RPO total will climb significantly. Wall Street analysts’ forecasts for the company’s 2026 revenue range from $10.9 billion to $14.9 billion, according to data compiled by LSEG.

Bulls argue that this is exactly how the boom will play out in CoreWeave’s favor: The revenue will come through, in great quantity, and its scale will solve the company’s problems by catching up with and then outpacing its capital expenditures. In that scenario, the company becomes the next Levi Strauss or Amazon Web Services, providing the “picks and shovels” of the AI boom, and getting filthy rich. “The potential is beyond the scope of our imagination at this point,” says Kevin Dede, a senior technology analyst at the financial services firm H.C. Wainwright, which rates CoreWeave a “buy.”

But for now CoreWeave is miles away from being profitable and is bleeding cash, absent its ability to issue debt. The RPOs it reported in its most recent earnings that are likely to be realized in the next 12 months are not, on their own, sufficient to cover its current obligations and announced growth plans (more on that shortly). The company has razor-thin operating margins—1.6% in the past quarter. After accounting for its large interest expenses, those margins turn sharply negative. The company lost more than $600 million on $2.2 billion in revenue in the first six months of 2025. “That’s not great,” Luria says. “Is there any way that gap closes?”

Barring an enormous surge in revenue over the next 12 months or so, the company will likely need to borrow more money, or renegotiate with creditors, in order to cover the obligations already on its books. To be sure, the AI boom could deliver that revenue surge—but even slight weakening in spending growth across the industry could hit CoreWeave disproportionately. Kerrisdale Capital, an investment management firm that is shorting the stock, is pithy in its conclusions: CoreWeave, it wrote in a September report, is “the poster child of the AI infrastructure bubble.”

A pivot to AI, fueled by debt

CoreWeave began as a crypto-mining company, a side project of a few friends who were hedge-fund traders. Crypto mining, like AI, relies heavily on graphic processing units, or GPUs, with the chips racing to solve complicated algorithms that spit out currency rewards for correctly verifying blockchain transactions, and CoreWeave was a steady buyer.

Over time, Brian Venturo, one of the company’s founders, realized that the rise in AI would be a major factor fueling the surge in demand for the computing power of the GPUs that CoreWeave was already accumulating. Beginning in October 2021, CoreWeave entered into two deals with asset management firm Magnetar Capital, raising first $50 million in convertible notes, and then a year later, an additional $125 million, also in convertible notes. The company used nearly all of it to buy GPUs from Nvidia. Over the next few years, CoreWeave would secure billions of dollars in a combination of debt and equity, building out a sprawling array of data centers across the U.S., and eventually expanding to the U.K.

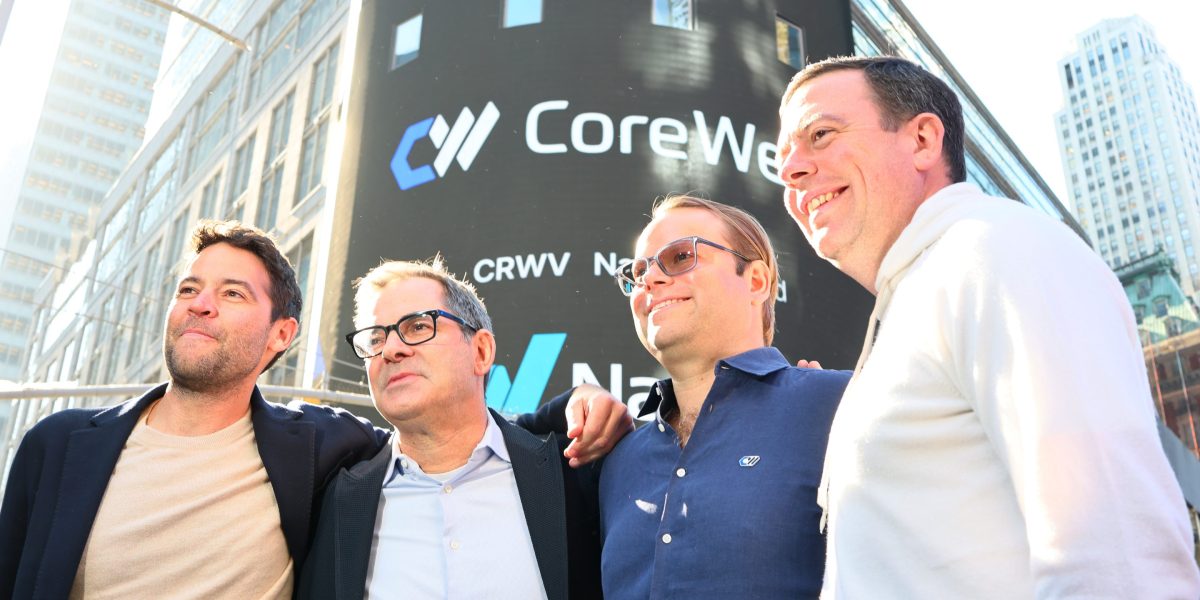

This March, CoreWeave’s IPO made it one of the closest things to a pure-play AI company to debut on public markets. Initially, fears about the company’s debt load restrained its stock’s performance. But its shares took off in May after it reported its first quarterly earnings, including soaring revenue growth of 420% quarter-on-quarter. While the price has declined since a peak in June, CoreWeave shares closed on Friday at $104, up from a debut of $40.

But as Luria puts it, the bear case for CoreWeave is simple math. The company’s business model is to borrow capital and then use that capital to build data centers filled with GPUs and then sell time on those GPUs to AI companies. “The question is, are they getting a sufficient return … on their investment to justify the interest they’re paying on their debt?” Luria says.

Its most recent filings show how hefty that debt has become. The problem isn’t just the amount of CoreWeave’s debt. It’s the structure—most of it is more expensive than average for corporate debt, and much of it comes due in the next nine months. Of CoreWeave’s current liabilities, $3.6 billion is debt payable by June 30, 2026, just part of $11 billion in overall debt the company carries on its balance sheet. Much of that debt carries hefty interest rates of between 9% and 15%, according to the financial statements, with 11% being the weighted average rate overall. (This fall, rates on newly issued investment-grade corporate debt have hovered between 5.5% and 6%, according to Moody’s. The rate at which CoreWeave is able to borrow has come down over time, with most of its newer debt issued at closer to 9%. )

The majority of CoreWeave’s outstanding debt, its statements show, is in the form of two loans, called Delayed Draw Term Loan (DDTL)1.0 and DDTL 2.0. There is $1.8 billion outstanding on the DDTL 1.0, at a 15% interest rate, and $5 billion in DDTL 2.0, at an 11% interest rate. The company has begun payment on DDTL 1.0; quarterly principal payments on DDTL 2.0 are due beginning in January 2026. (The interest rates on both these loans are floating.)

This is where the company’s RPOs come in. CoreWeave says that as of June 30 it had a little over $30 billion, the majority of which should turn into actual sales over the next four years. The company says 50% of that amount, or $15 billion, will be recognized in the next two years. Assuming half of that will in turn be recognized in the next year, that means the company should have $7.5 billion coming in. But if its operating margins remain at just 1.6%, the company will only generate $120 million in income from this $7.5 billion—not enough to cover its interest expenses or make the principal repayments on its debt. That implies that CoreWeave’s returns remain far below the cost of its capital.

Higher RPOs, of course, would mean more revenue for CoreWeave next year. That said, there are also far more capital expenses to come. CoreWeave continues to spend heavily to purchase Nvidia GPUs—which make up the great majority of its capital expenditures—and other equipment to outfit its data centers. In the first half of 2025, for example, it invested $4.7 billion in property, plant and equipment while bringing in only $2.2 billion in revenue. The report from Kerrisdale cites similar concerns as Luria in justifying its short position. CoreWeave is “a debt-fueled GPU rental business with no moat, dressed up as innovation,” the firm writes, arguing that the stock faces a 90% downside.

Can CoreWeave count on its customers?

Luria and Kerrisdale both cite CoreWeave’s highly concentrated customer base as another potential peril—a reality that CoreWeave itself acknowledged in its last earnings report. “A substantial portion of our revenue is driven by a limited number of our customers, and the loss of, or a significant reduction in, spend from one or a few of our top customers would adversely affect our business,” the company wrote. Most notably: In the second quarter of 2025, an eye-popping 71% of CoreWeave’s revenue came from Microsoft alone.

To be sure, Microsoft has a better credit rating than many countries, including the United States, and is unlikely to renege on its contract with CoreWeave. And CoreWeave’s contracts with its lessees generally require them to pay to the ends of their leases even if they don’t wind up utilizing them, except in case of “nonperformance.”

Much of CoreWeave’s utility has come from offering readily available compute as those companies raced to scale up their own operations. But with Microsoft set to spend tens of billions of dollars on developing its own data centers, it may not need CoreWeave’s services in the future. “They will pay their obligations, but the likelihood of them renewing at the end of the contract is much less guaranteed,” Luria says.

CoreWeave’s other major customer, OpenAI, is another matter. In March, CoreWeave entered an agreement with Sam Altman’s AI giant, with OpenAI committed to paying $11.9 billion through October 2030, with a $4 billion expansion announced in May. But OpenAI itself has made commitments far beyond its current cash flow—including commitments in the many hundreds of billions to Oracle, Nvidia and other data center providers.

If OpenAI runs into any financial troubles, Luria says, CoreWeave likely wouldn’t be first to receive payments, compared to much larger OpenAI partners like Microsoft, Amazon, or even Oracle. (That’s also the case for some of the other, smaller venture-backed and loss-making AI startups CoreWeave serves, such as poolside, Cohere, and Mistral.) To rely on CoreWeave’s ties to OpenAI, he says, “You have to believe that OpenAI is going to be unbelievably successful, so much so that it can pay everybody that’s ahead in line.”

All eyes on earnings

All of this means there’ll be plenty at stake when CoreWeave reports earnings on Monday. The company will also be digesting a recent setback: In late October, the shareholders of Core Scientific, a crypto miner with a hoard of computing resources that CoreWeave coveted, rejected CoreWeave’s $9 billion all-stock acquisition offer. (CoreWeave will console itself with a $270 million breakup fee—an amount that will help it cover the $360 million it is expected to pay Core Scientific to lease data center capacity from it next year. Overall, CoreWeave is on the hook to pay Core Scientific some $10 billion in future lease payments over the next 12 years, which may have been one reason CoreWeave was eager to try to use its highly-valued shares to purchase Core Scientific in an all-equity deal valued at $9 billion when the offer was initially made.)

The argument for CoreWeave’s success is just as simple as the math against it: AI is going to represent a transformational shift in the global economy, and CoreWeave is powering the technology’s growth. As the development of AI accelerates, so will the demand for computing power from companies aside from the hyperscalers, all hungry for the services of providers like CoreWeave. What’s more, today’s creditors may be willing to wait a little longer for that demand to materialize: The lenders behind DDTL 2.0 recently renegotiated the terms of the loan to delay the start of principal payments.

Blakely, at Cantor Fitzgerald, says that CoreWeave is already diversifying its customer base, noting the recent deal with Meta. “It’s a growth business,” he says, in reference to CoreWeave’s capital expenditures. “If business is growing, you have to invest against it.” He and other bulls see a future where the company is no longer laden with debt. Once CoreWeave sheds its liabilities over the next five years, Blakely says, a growing percent of its revenue can begin coming from infrastructure that’s already paid off, boosting CoreWeave’s margins. Moreover, Blakely says that new models of chips might run more efficiently or be able to fetch a higher premium from customers, allowing CoreWeave to hold more pricing power.

Blakely says that those $30.1 billion in RPOs—the revenue that has been booked but not yet delivered—are likely to increase meaningfully in CoreWeave’s next earnings, based on recently announced agreements. But the number to watch might be the additional obligations in borrowing that the company will take on to service them: If those obligations scale up alongside the booked revenue, bears say, CoreWeave still risks running out of cash unless it takes on yet more debt, raises more equity, or gets existing creditors to extend terms.

Blakely acknowledges that a sustainable path forward for CoreWeave is perilous. “A lot has to go right,” he says. Still, he compares the current moment in AI to the beginning of the smartphone era, where analysts doubted Apple’s claims that it would transform global communication. “CoreWeave is a leader there in terms of this market,” Blakely says. “If they can maintain that lead … they will be able to participate in the spoils.”

CORRECTION: An earlier version of this story stated incorrectly that Coreweave’s quarterly principal payments for DDTL 1.0 would begin in January 2026; those payments have already begun.

This article was updated to add a range of analysts’ projections for CoreWeave’s 2026 revenue.

You may like

Business

Epstein grand jury documents from Florida can be released by DOJ, judge rules

Published

8 minutes agoon

December 6, 2025By

Jace Porter

A federal judge on Friday gave the Justice Department permission to release transcripts of a grand jury investigation into Jeffrey Epstein’s abuse of underage girls in Florida — a case that ultimately ended without any federal charges being filed against the millionaire sex offender.

U.S. District Judge Rodney Smith said a recently passed federal law ordering the release of records related to Epstein overrode the usual rules about grand jury secrecy.

The law signed in November by President Donald Trump compels the Justice Department, FBI and federal prosecutors to release later this month the vast troves of material they have amassed during investigations into Epstein that date back at least two decades.

Friday’s court ruling dealt with the earliest known federal inquiry.

In 2005, police in Palm Beach, Florida, where Epstein had a mansion, began interviewing teenage girls who told of being hired to give the financier sexualized massages. The FBI later joined the investigation.

Federal prosecutors in Florida prepared an indictment in 2007, but Epstein’s lawyers attacked the credibility of his accusers publicly while secretly negotiating a plea bargain that would let him avoid serious jail time.

In 2008, Epstein pleaded guilty to relatively minor state charges of soliciting prostitution from someone under age 18. He served most of his 18-month sentence in a work release program that let him spend his days in his office.

The U.S. attorney in Miami at the time, Alex Acosta, agreed not to prosecute Epstein on federal charges — a decision that outraged Epstein’s accusers. After the Miami Herald reexamined the unusual plea bargain in a series of stories in 2018, public outrage over Epstein’s light sentence led to Acosta’s resignation as Trump’s labor secretary.

A Justice Department report in 2020 found that Acosta exercised “poor judgment” in handling the investigation, but it also said he did not engage in professional misconduct.

A different federal prosecutor, in New York, brought a sex trafficking indictment against Epstein in 2019, mirroring some of the same allegations involving underage girls that had been the subject of the aborted investigation. Epstein killed himself while awaiting trial. His longtime confidant and ex-girlfriend, Ghislaine Maxwell, was then tried on similar charges, convicted and sentenced in 2022 to 20 years in prison.

Transcripts of the grand jury proceedings from the aborted federal case in Florida could shed more light on federal prosecutors’ decision not to go forward with it. Records related to state grand jury proceedings have already been made public.

When the documents will be released is unknown. The Justice Department asked the court to unseal them so they could be released with other records required to be disclosed under the Epstein Files Transparency Act. The Justice Department hasn’t set a timetable for when it plans to start releasing information, but the law set a deadline of Dec. 19.

The law also allows the Justice Department to withhold files that it says could jeopardize an active federal investigation. Files can also be withheld if they’re found to be classified or if they pertain to national defense or foreign policy.

One of the federal prosecutors on the Florida case did not answer a phone call Friday and the other declined to answer questions.

A judge had previously declined to release the grand jury records, citing the usual rules about grand jury secrecy, but Smith said the new federal law allowed public disclosure.

The Justice Department has separate requests pending for the release of grand jury records related to the sex trafficking cases against Epstein and Maxwell in New York. The judges in those matters have said they plan to rule expeditiously.

___

Sisak reported from New York.

Business

Miss Universe co-owner gets bank accounts frozen as part of probe into drugs, fuel and arms trafficking

Published

39 minutes agoon

December 6, 2025By

Jace Porter

Mexico’s anti-money laundering office has frozen the bank accounts of the Mexican co-owner of Miss Universe as part of an investigation into drugs, fuel and arms trafficking, an official said Friday.

The country’s Financial Intelligence Unit, which oversees the fight against money laundering, froze Mexican businessman Raúl Rocha Cantú’s bank accounts in Mexico, a federal official told The Associated Press on condition of anonymity because he was not authorized to comment on the investigation.

The action against Rocha Cantú adds to mounting controversies for the Miss Universe organization. Last week, a court in Thailand issued an arrest warrant for the Thai co-owner of the Miss Universe Organization in connection with a fraud case and this year’s competition — won by Miss Mexico Fatima Bosch — faced allegations of rigging.

The Miss Universe organization did not immediately respond to an email from The Associated Press seeking comment about the allegations against Rocha Cantú.

Mexico’s federal prosecutors said last week that Rocha Cantú has been under investigation since November 2024 for alleged organized crime activity, including drug and arms trafficking, as well as fuel theft. Last month, a federal judge issued 13 arrest warrants for some of those involved in the case, including the Mexican businessman, whose company Legacy Holding Group USA owns 50% of the Miss Universe shares.

The organization’s other 50% belongs to JKN Global Group Public Co. Ltd., a company owned by Jakkaphong “Anne” Jakrajutatip.

A Thai court last week issued an arrest warrant for Jakrajutatip who was released on bail in 2023 on the fraud case. She failed to appear as required in a Bangkok court on Nov. 25. Since she did not notify the court about her absence, she was deemed to be a flight risk, according to a statement from the Bangkok South District Court.

The court rescheduled her hearing for Dec. 26.

Rocha Cantú was also a part owner of the Casino Royale in the northern Mexican city of Monterrey, when it was attacked in 2011 by a group of gunmen who entered it, doused gasoline and set it on fire, killing 52 people.

Baltazar Saucedo Estrada, who was charged with planning the attack, was sentenced in July to 135 years in prison.

Business

Elon Musk’s X fined $140 million by EU for breaching digital regulations

Published

1 hour agoon

December 6, 2025By

Jace Porter

European Union regulators on Friday fined X, Elon Musk’s social media platform, 120 million euros ($140 million) for breaches of the bloc’s digital regulations, in a move that risks rekindling tensions with Washington over free speech.

The European Commission issued its decision following an investigation it opened two years ago into X under the 27-nation bloc’s Digital Services Act, also known as the DSA.

It’s the first time that the EU has issued a so-called non-compliance decision since rolling out the DSA. The sweeping rulebook requires platforms to take more responsibility for protecting European users and cleaning up harmful or illegal content and products on their sites, under threat of hefty fines.

The Commission, the bloc’s executive arm, said it was punishing X because of three different breaches of the DSA’s transparency requirements. The decision could rile President Donald Trump, whose administration has lashed out at digital regulations, complained that Brussels was targeting U.S. tech companies and vowed to retaliate.

U.S. Secretary of State Marco Rubio posted on his X account that the Commission’s fine was akin to an attack on the American people. Musk later agreed with Rubio’s sentiment.

“The European Commission’s $140 million fine isn’t just an attack on @X, it’s an attack on all American tech platforms and the American people by foreign governments,” Rubio wrote. “The days of censoring Americans online are over.”

Vice President JD Vance, posting on X ahead of the decision, accused the Commission of seeking to fine X “for not engaging in censorship.”

“The EU should be supporting free speech not attacking American companies over garbage,” he wrote.

Officials denied the rules were intended to muzzle Big Tech companies. The Commission is “not targeting anyone, not targeting any company, not targeting any jurisdictions based on their color or their country of origin,” spokesman Thomas Regnier told a regular briefing in Brussels. “Absolutely not. This is based on a process, democratic process.”

X did not respond immediately to an email request for comment.

EU regulators had already outlined their accusations in mid-2024 when they released preliminary findings of their investigation into X.

Regulators said X’s blue checkmarks broke the rules because on “deceptive design practices” and could expose users to scams and manipulation.

Before Musk acquired X, when it was previously known as Twitter, the checkmarks mirrored verification badges common on social media and were largely reserved for celebrities, politicians and other influential accounts, such as Beyonce, Pope Francis, writer Neil Gaiman and rapper Lil Nas X.

After he bought it in 2022, the site started issuing the badges to anyone who wanted to pay $8 per month.

That means X does not meaningfully verify who’s behind the account, “making it difficult for users to judge the authenticity of accounts and content they engage with,” the Commission said in its announcement.

X also fell short of the transparency requirements for its ad database, regulators said.

Platforms in the EU are required to provide a database of all the digital advertisements they have carried, with details such as who paid for them and the intended audience, to help researches detect scams, fake ads and coordinated influence campaigns. But X’s database, the Commission said, is undermined by design features and access barriers such as “excessive delays in processing.”

Regulators also said X also puts up “unnecessary barriers” for researchers trying to access public data, which stymies research into systemic risks that European users face.

“Deceiving users with blue checkmarks, obscuring information on ads and shutting out researchers have no place online in the EU. The DSA protects users,” Henna Virkkunen, the EU’s executive vice-president for tech sovereignty, security and democracy, said in a prepared statement.

The Commission also wrapped up a separate DSA case Friday involving TikTok’s ad database after the video-sharing platform promised to make changes to ensure full transparency.

___

AP Writer Lorne Cook in Brussels contributed to this report.

Epstein grand jury documents from Florida can be released by DOJ, judge rules

National Guardsman’s Head Wound Slowly Healing After D.C. Shooting

Miss Universe co-owner gets bank accounts frozen as part of probe into drugs, fuel and arms trafficking

Trending

-

Politics8 years ago

Politics8 years agoCongress rolls out ‘Better Deal,’ new economic agenda

-

Entertainment8 years ago

Entertainment8 years agoNew Season 8 Walking Dead trailer flashes forward in time

-

Politics8 years ago

Politics8 years agoPoll: Virginia governor’s race in dead heat

-

Entertainment8 years ago

Entertainment8 years agoThe final 6 ‘Game of Thrones’ episodes might feel like a full season

-

Entertainment8 years ago

Entertainment8 years agoMeet Superman’s grandfather in new trailer for Krypton

-

Politics8 years ago

Politics8 years agoIllinois’ financial crisis could bring the state to a halt

-

Business8 years ago

Business8 years ago6 Stunning new co-working spaces around the globe

-

Tech8 years ago

Tech8 years agoHulu hires Google marketing veteran Kelly Campbell as CMO