Business

Wells Fargo was reeling from scandal. Jamie Dimon protégé Charlie Scharf bet his career on saving the 173-year-old bank

Published

2 months agoon

By

Jace Porter

The document, Charlie Scharf recalls, was 3,162 pages. It included 6,000 tasks; 28,000 people worked on it. This staggeringly long volume was the plan to save Wells Fargo, forged by Scharf and his team shortly after he took over as CEO in October 2019.

At the time, Wells had been laboring under a regulatory crackdown unleashed by the cataclysm that blackened the formerly burnished Wells name, the heavily publicized scandal revealing that the bank had bilked millions of customers by creating fake and unneeded accounts at its branches. That culminated in a draconian penalty imposed by the Federal Reserve: a hard limit on its total assets that essentially blocked Wells from raising the deposits that form the lifeblood of banking.

The process was grueling. Scharf recalls that every Monday morning, he would lead a two-hour meeting of the 15-member operating committee in which they laboriously worked through where their departments stood on reaching their goals. “Charlie would go around the table asking, ‘Why are you missing these dates? Why are we falling behind?’” relates one of the brain trust subject to the grillings. He’d relentlessly demand that executives who were lagging come back next week with a formula to course correct, and catch up. Those who couldn’t keep up didn’t last long.

In the early going, Scharf would get harshly worded emails from the regulators demanding more progress. “I just lived it all week, and on Friday afternoons I’d often get this official correspondence from regulators,” he recalls. “The language was jarring. I didn’t want to work on Friday night unless I had to. I wanted to take time with my family and decompress. So I would say, I’m not going to open these things until Saturday or sometimes Sunday.”

The task of saving the institution looked beyond daunting. Investors big and small took a dim view of its prospects. Warren Buffett, whose Berkshire Hathaway had been a big Wells investor for two decades, slammed the prior top management for “ignoring [the sales fiasco] when they found out about it,” and dumped his entire stake. From February 2018 to December 2020, its share price dropped by two-thirds, shaving its market cap from $322 billion to $88 billion. Calls in Congress for a breakup were rising; Sen. Elizabeth Warren (D-Mass.) demanded that the bank split into units that could more readily comply with banking norms, and Sen. Sherrod Brown (D-Ohio) trashed Wells as “too big to manage.”

Scharf admits that as a banker, he’d never faced anything remotely as tough as the mission at Wells. “I remember knowing what I was getting myself into, but it was much worse directionally than I thought … The regulatory pressure was beyond anything I’ve experienced, and so was the political pressure,” the CEO avows. Indeed, brought in to enact a turnaround, Scharf was facing rising odds that regulators could dismantle one of America’s most legendary financial institutions.

Scharf had been training for this job his whole life

Scharf is perched on a couch in his office, framed by floor-to-ceiling windows overlooking the southward sweep of the Wall Street district where he worked as a teenager, the Statue of Liberty a copper-green miniature in the distance. He’s attired in jeans and tan sneakers, his short white hair perfectly coiffed, sans his usual, virtually trademark owl-lens glasses.

The Wells Fargo rescue job suited Scharf for a basic reason: He’d been training for a task just like this one all his working life. He practically grew up in the Wall Street engine room. Scharf’s dad was a stockbroker who eventually worked for Sandy Weill at Smith Barney, and was still there when his son became the firm’s CFO in 1995. Starting at age 13, Charlie during the summers would commute with his father from the family home in Westfield, N.J., a tony suburb 20 minutes west of Newark Airport, to the elder Scharf’s brokerage house. “We’d get off the train at the World Trade Center, and he’d go to his building and I’d go to mine,” he recalls. The young Scharf’s various posts included such back-office positions as inputting data and working in the securities vault.

As a senior at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, Scharf started interviewing at prestigious financial firms in Manhattan when his father recommended an oddball choice that set his professional trajectory. “He said, ‘This amazing guy named Sandy Weill has built a great management team at this tiny company called Commercial Credit in Baltimore, and I don’t know what it is, but they’re going to do great things, and you should be with great people.’” His father had a cousin who knew Jamie Dimon’s dad and managed to get Charlie’s résumé to Dimon, the consumer finance purveyor’s CFO.

One day in March 1987, Scharf spent an afternoon at Commercial Credit, interviewing with Dimon and several other executives. “Before I left, Jamie comes to the waiting room and tells me, ‘We’re going to offer you a job.’ I later learned that by hiring me on the spot, he wanted to prove a point, that Commercial Credit was no longer a slow-moving company that hadn’t hired young people for years.” For his part, Dimon remembers that Scharf even as a youngster wasn’t easy to please. “I kept sending him around to different jobs, and almost everywhere he went he’d come back, and I’d say, ‘How are you doing?’ and he’d say, ‘This area is screwed up, this area is terrible,’ he was always pretty critical. So I said, ‘Okay, kid, you’re going to work for me as my assistant. I want to see what you’ve got.’”

The frat house vibe at Commercial Credit stunned the green recruit. “Neither the offices nor Jamie looked like anything out of corporate America,” marvels Scharf. The staff lounged on worn red velour couches, the fax machine was always on the blink, and the AC system was so old it hissed loudly, when it cooled at all. “People were walking around smoking, it was the era,” says Scott Powell, Wells’ COO and a fellow youngster at the firm in those days. Nicknamed “the Kid,” Dimon sported an unruly head of hair that matched his fireball personality. Remembers Scharf, Dimon would bark commands into “a giant, outdated squawk box like the one in Charlie’s Angels.” The Dimon and Weill means of communication, says Scharf, was to scream at each other until they reached consensus.

A series of roles with more responsibilities followed—including following Dimon to Bank One in Chicago after his famous falling out with Weill. Finally in 2012 Visa came calling and made Scharf its CEO, a role he excelled at before leaving suddenly to, as he says, to help a close family member navigate a difficult life journey, adding that “When CEOs say they left ‘for personal reasons,’ it usually means they were fired or fooling around. But for me, it really was personal reasons,” he says. “And I’ll never regret it.”

Scharf learned big-time from Dimon’s intensive, super-detailed, hands-on-all-the-levers management style, but it’s his ex-boss’s personal qualities that most impressed and influenced him. “What I came to realize through the years is that there’s a big difference between being a good manager and a good leader,” he avows. “Being a good leader means you inspire people by what you’re doing and how you do it, how you carry yourself, that they want to follow you into extremely tough jobs simply because they believe in you. That’s Jamie.”

While Dimon is highly theatrical, Scharf seldom raises his voice in meetings, even when he’s unhappy. “What he’s really good at is lowering the temperature to find solutions,” says someone who’s worked with Scharf.

Still, Scharf’s just as tough and blunt as Dimon. “He doesn’t waste time trying to make people feel good when he makes a tough decision. He moved people out quickly, with no anguish,” says someone who knows him well. A familiar refrain is that he will not shy away from “calling people on their BS.” Don’t look for flexibility if you’re not hitting profit and performance goals, say managers in his orbit. “Charlie is very measured,” says Fernando Rivas, head of corporate and investment banking at Wells, “but he’s uncompromising on outcomes and values.”

Observes a person who’s worked with Scharf: “The strange thing about him is, a lot of people are kind and nice on the surface but colder below. Charlie is just the opposite. On the surface he can be intimidating, but go a tiny bit below and you find a sweet, caring person.”

How Wells Fargo lost its way

The Wells Fargo he inherited, however, was a basket case. Having skirted the Global Financial Crisis with its mix of “Main Street, not Wall Street” basics for everyday Americans and their businesses—in fact, Wells greatly benefited from the meltdown via its emergency purchase of failing Wachovia—the bank by the close of 2012 boasted the highest market cap of any U.S. megabank.

Then the troubles began.

Post GFC, regulators wanted all banks to tighten up compliance. Prior Wells management proved totally incapable of instituting the broad infrastructure required to tightly manage risk. “It probably was hubris from avoiding the problems in the GFC,” says COO Powell. A House Financial Services Committee Staff Report from early 2020 reached the same conclusion, quoting an emergency hire helicoptered in from J.P. Morgan who said she found the controls “immature and inadequate,” and regulators skewered the managers in charge for showing “no sense of urgency” in fixing them. Wells had historically been a highly decentralized complex assembled from sundry mergers and acquisitions—management used the adage “80 horses pulling the stagecoach.”

The chief risk officer was unable to impose unified standards across the fiefdoms. “They were farming out all risk management to individual businesses,” and using manual processes that were a decade old, says Wells lead director Steve Black. “And they were in quicksand trying to fix it.” The House report refers to the then chief risk officer as vainly “attempting to cajole and persuade” the consumer chief to adhere to overall rules, and getting nowhere.

The “fake accounts” disaster—in which congressional investigations found that Wells deployed a high-pressure culture of “cross-selling” that rewarded branch bankers for opening multiple accounts that customers knew nothing about—cost Wells over $8 billion in fines. In its press release, the Justice Department skewered past management for “complete failure of leadership at multiple levels” and the “staggering size, scope and duration of Wells Fargo’s illicit conduct”; 5,000 alleged abusers were fired from 2011 to 2016. In 2017, regulators forced the CEO and head of the consumer bank to resign, and clawed back a total of $69 million in their compensation.

Scharf won the confidence of regulators, in part, by making himself the point person at Wells. “We had a formal meeting with all three regulators once a month, but I’d personally call the officials in charge of all three practically every week, often multiple times. I wanted them to see how seriously we were taking this, which was not the case before I arrived. I also wanted to set an example for the other executives, that I’m not going to ask them to spend more time with regulators unless I did it myself.”

To implement the changes, Scharf recruited a crack new team who’d installed and worked under the kinds of controls Wells needed. All but two of the operating committee’s 15 members are Scharf hires, many of whom won his trust earlier in his career, and the pair on the top team who worked at Wells when Scharf arrived now fill new roles. A key addition was COO Powell, whom Scharf worked with at Bank One and J.P. Morgan, and who’s a seasoned expert at installing just the kind of discipline Wells needed. Surprisingly, Scharf named as chief risk officer not an outsider, but a Wells veteran. Derek Flowers caught the CEO’s eye for his expert work as a credit risk manager in various divisions, and he’s proven a whiz, says Scharf, at the corporate CRO job that also encompasses operations and compliance. Flowers reports directly to Scharf and the board’s audit committee. “The best executives at Wells were not at the top but the mid and upper-mid level, and we promoted many of them, including Derek,” says Scharf. “And that builds confidence with the troops, because they know who the good people are.” Scharf also lavished resources on creating the intricate, extensive architecture required to satisfy the consent orders, and maintain the new superstructure. Today, Wells spends $2.5 billion more a year on risk management than when Scharf took charge (that’s about 3% of total expenses). Scharf has raised the number of risk managers stationed in business units by 10,000, an addition that doubled the total workforce monitoring credit, operations, and compliance.

For seven years, the ceiling that restricted holdings of deposits and securities to $1.95 trillion forced Wells to reject gigantic amounts of customer cash. “I’d estimate that we left $600 billion on the table,” reckons Scharf. In that span, J.P. Morgan, Bank of America, and Citi have respectively grown their balance sheets 58%, 40%, and 34%. As a result, net interest income at Wells, a huge revenue line for banks, pretty much treaded water while that metric jumped for its competitors.

But Scharf didn’t stand still. He developed an overarching strategy to grow promising franchises where Wells had way underinvested. The idea: Raise fee income—a category that wasn’t limited—to offset the decline or flattening in interest revenues in big swaths of the bank necessitated by the asset limit.

Keeping assets fixed per the caps required some unwelcome maneuvers, explains Rivas, the corporate and investment banking chief at Wells who long served as Scharf’s top M&A advisor, and whom the CEO recruited from a top job at J.P. Morgan. “Asking customers, ‘Will you please take your deposits elsewhere?’ is an unnatural thing for a bank to do,” declares Rivas.

Though Wells had long boasted that “we’re kitchen table, not league tables,” Scharf trained a spotlight on investment banking. Moving the C-suite from San Francisco to Manhattan helped. Most of all, the commercial bank—virtually tied for largest in the nation with J.P. Morgan—was serving scores of companies that needed advice in purchasing other family companies, for example, or in raising fresh equity or debt financing.

Then Scharf trained his sights on credit cards. “Pre-pandemic, Wells was way off base in the crucial premium credit card space; they weren’t showing any pulse,” says Brian Kelly, founder of the Points Guy travel site. One problem was that Wells had poor fraud detection models, so it was frequently turning down transactions it should have safely approved, greatly annoying especially wealthy clients, Scharf included. “I was at dinner in London with my wife and friends, and I go to pay, and my card gets rejected,” he recalls. In addition, Wells lacked the expertise to grant the high-net-worth crowd sufficiently generous lines of credit.

Scharf channeled big investments into the previously undernourished division, even green-lighting the comedic ad series featuring Steve Martin and Martin Short, and funding the IT upgrades that solved the credit lines problem, as well as finding the analytical sweet spot for accepting or declining charges. Though there have been stumbles—such as a Bilt cobranded card to pay for rent that flopped—even that gave Wells much-needed exposure to Gen Z. From 2020 to 2024 overall purchase volumes and card balances outstanding have both doubled. “Some people would say they’re crazy to compete with Amex and Chase, that have huge technology and interaction,” says Dimon. “But Wells has a competitive advantage, they have a huge client base of over 40 million customers, what I call a ‘warm market,’ so they should.”

Meanwhile, Scharf was targeting deep cuts in spending—seeking out from his previous experience places where “two layers,” one superfluous and bureaucratic, had been allowed to coexist within a giant corporation. “We saw it at Citigroup, at the former J.P. Morgan, at Travelers. At Wells, we had extra layers, the same work being done in two businesses that could have been centralized, including HR, legal, IT, and other areas,” he says.

Scharf demanded that all high-ranking executives have at least seven direct reports, double the previous number. Wells was swimming in unused real estate. In Minneapolis, Des Moines, and several other cities, its workforce was often spread across multiple small and often aging facilities. From 2019 to the close of 2024, the bank reduced its global footprint from 87 million square feet to 60.3 million, and shrank the office building count from 650 to 400, by concentrating employees in bigger, newer locations. When Scharf arrived, Wells had three-quarters of J.P. Morgan’s revenues but 6% more employees. Under Scharf, Wells’ headcount has declined by almost 25% to 210,000. He consciously downshifted in areas such as home loans, which became less profitable given higher capital requirements following the GFC, and held “reputational risk” he didn’t want should foreclosures spike.

Going forward, Scharf’s holy grail is return on tangible common equity or ROTCE, essentially the cents an enterprise gives shareholders for every dollar they invest. Last year, Wells hit 13.4%. That figure waxed Citigroup (7%), pretty much tied BofA, and fell well short of J.P. Morgan’s 20%. Several years ago, Scharf set a goal of 15% that then looked highly aspirational. But he’s almost there, hitting 14.4% on average for the first two quarters of 2025. For Scharf, getting to 15% is just a way station. He’s aiming to charge toward the industry-topping, J.P. Morgan–style summit.

The magnitude of the changes Scharf made became evident in May of this year, when he got one of the most important phone calls of his life. It was a congratulatory overture from a top Fed official whom he declines to name who delivered the news that the central bank would soon be lifting the limit on assets, effectively restoring full freedom of movement to an institution shackled for years. When the official announcement came on June 3, the CEO and several lieutenants gathered outside his office to sip Champagne and cheer the news. The air was thick with celebration, but also relief.

That’s not to say the job is done. John McDonald, an analyst at Truist Securities, likens Wells’ next act to this: “Wells had to lose weight, and Charlie got them on a diet. Now they’re at the gym and need to build muscle.”

Scharf has taken the stock from $52 when he started to $81 as of early October. Including strong dividends, Wells generated a 11.1% annual return since he took charge six years ago, well below J.P. Morgan’s 198.7% but practically matching BofA (11.2%) and beating Citi (9.2%), and a beat on the KBW Bank Index at 10.0%.

“If you look at where Wells was when he arrived and where it is now, not many people could have done what he did,” says Frank Bisignano, a colleague from J.P. Morgan and former CEO of payments colossus Fiserv who’s now commissioner of the Social Security Administration and chief executive officer of the IRS. “He was brave to take the job. You look at great coaches, they bring their coaching staffs with them. That’s what Charlie did at Wells, and it’s a sign of great leadership.”

Freed from the worst days of the Wells saga, Scharf is palpably grateful for the moments he has with his family, his daughter’s upcoming wedding, the weekends on Long Island in Remsenburg, a bayfront village well west of the Hamptons glamour zone, where he seldom runs into competitors and employees at the hotspots. He unwinds by practicing woodworking in his shop on the property, an activity he finds “soothing.” He prides himself on fashioning raised moldings and custom bookshelves. Dimon jokes that Scharf’s probably the only corporate chieftain who unwinds in a woodshop.

But his old mentor Dimon has high praise for the job Scharf has done. “The world is his oyster now that the asset cap is lifted and Wells can once again focus on growth. Charlie did an excellent job,” says this renowned truth-teller. But Dimon can’t resist adding one final bit of roasting for his friend and protégé of 30-plus years. “Though,” he says with a grin, “I probably would have wanted to do it faster.” Six thousand tasks later, Charlie Scharf did it on his own timeline. And the stagecoach is rolling again.

You may like

Business

Warren Buffett: Business titan and cover star

Published

45 minutes agoon

December 7, 2025By

Jace Porter

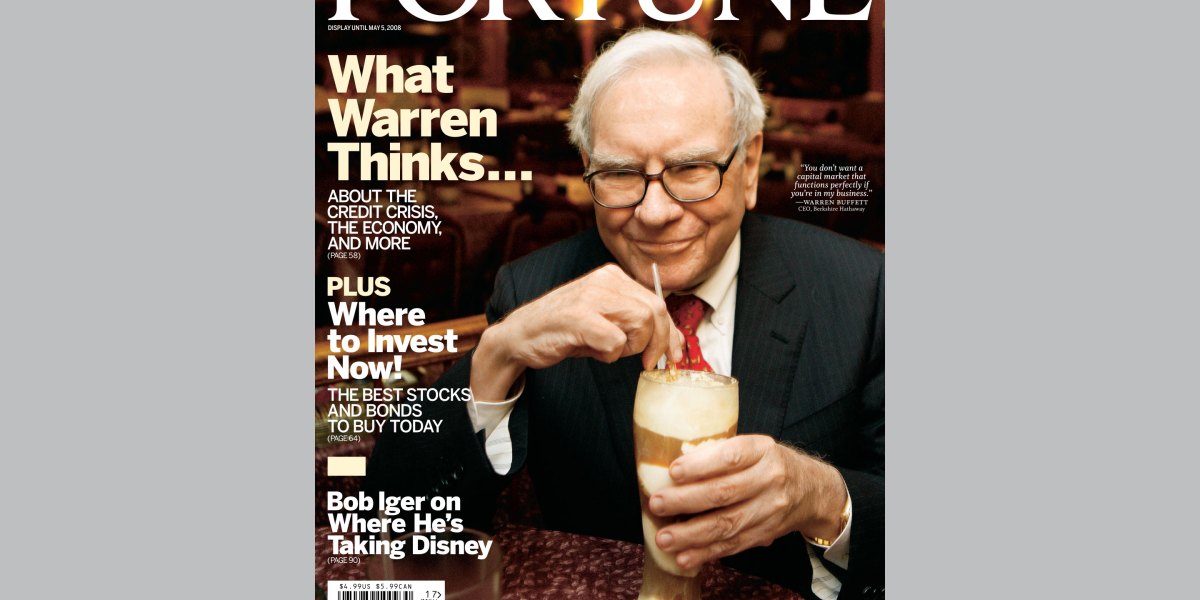

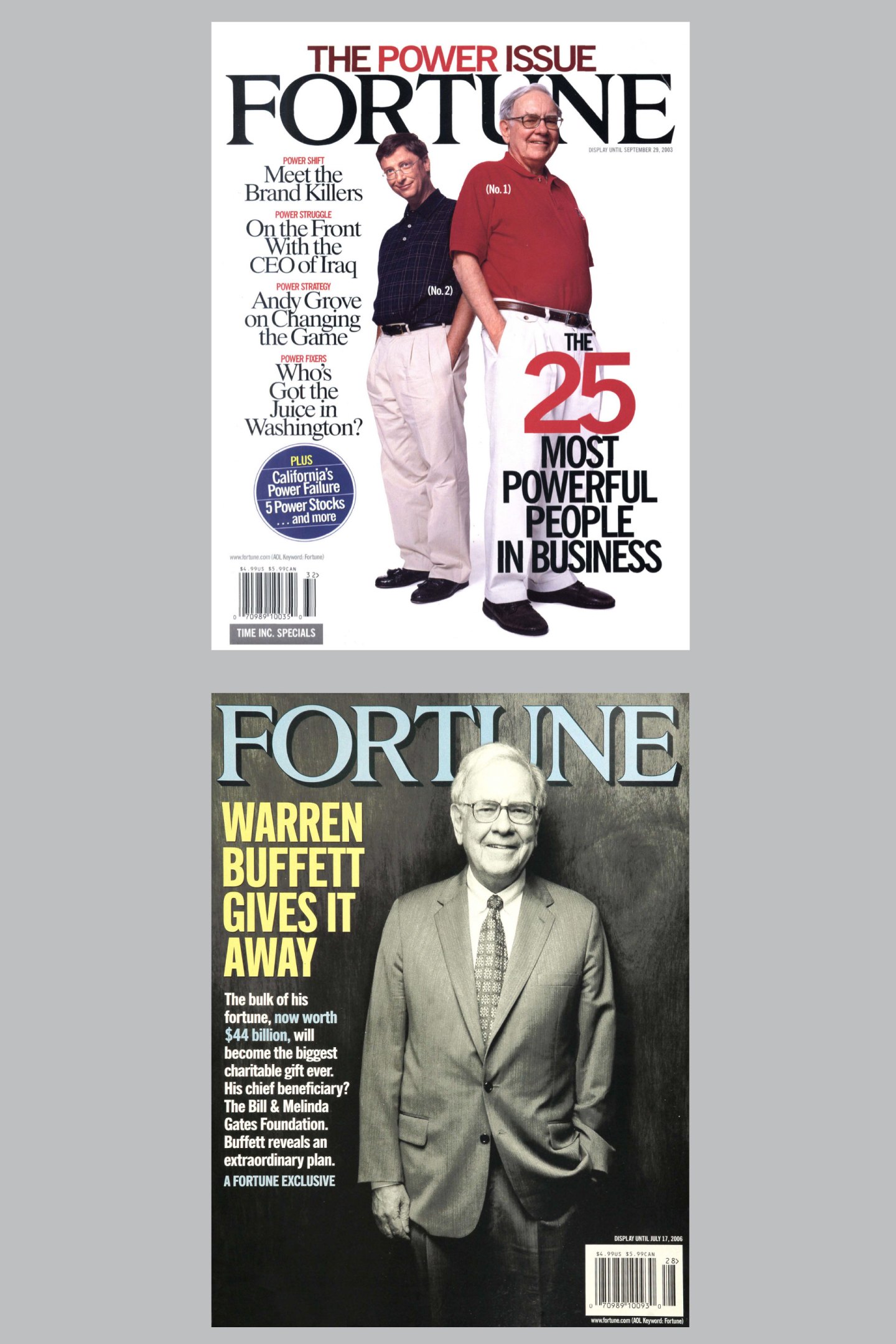

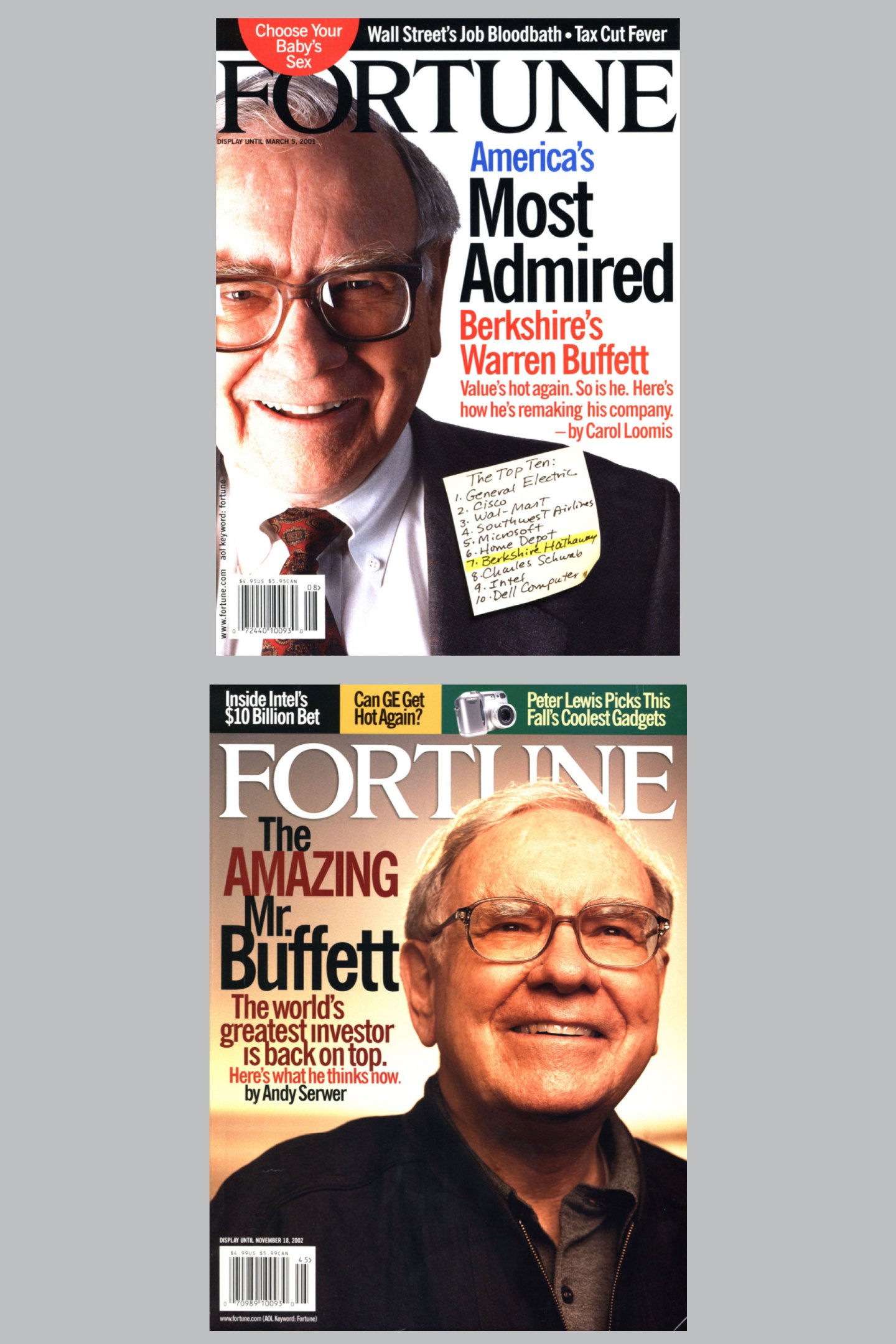

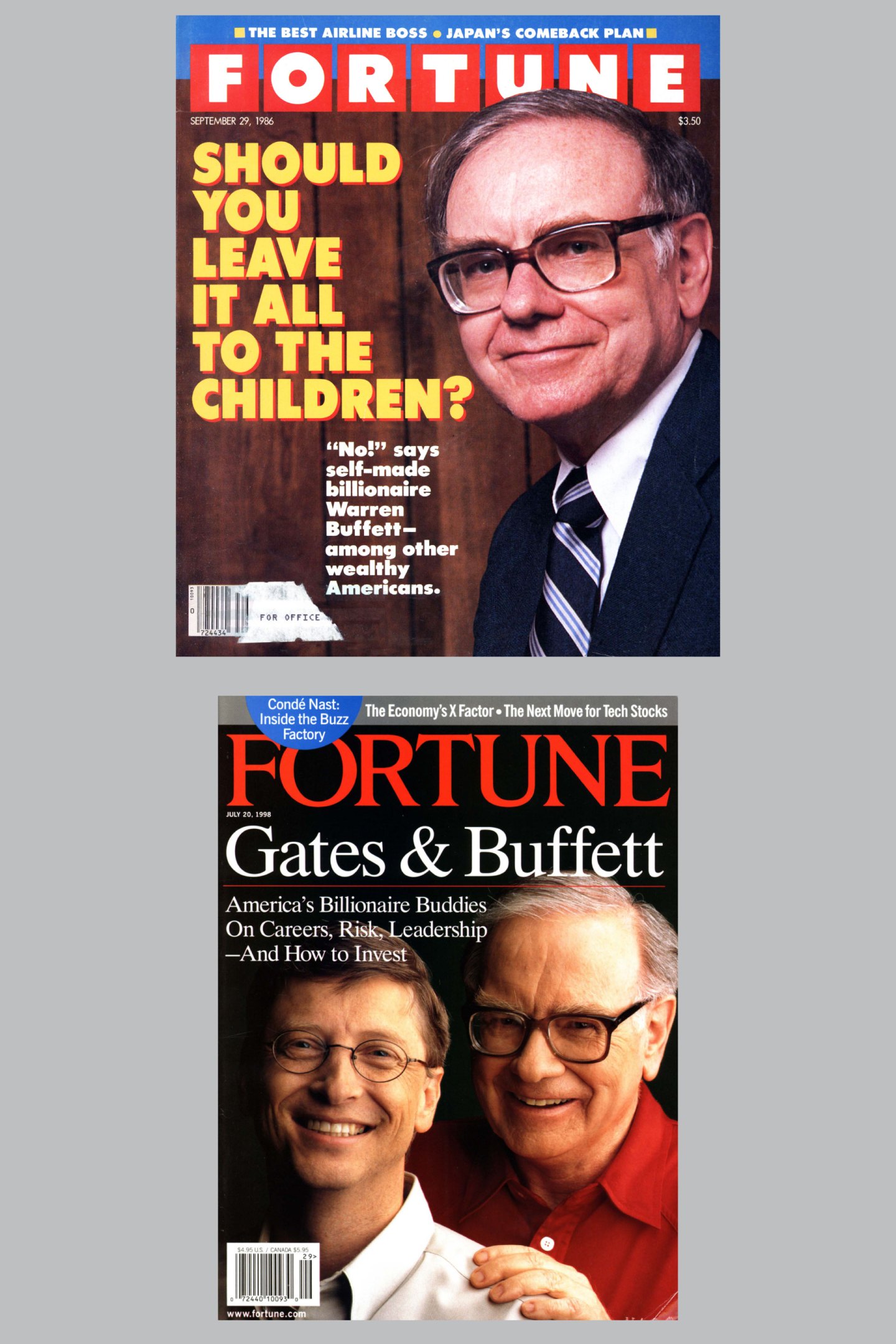

Warren Buffett’s face—always smiling, whether he’s slurping a milkshake, brandishing a lasso, or palling around with fellow multibillionaire Bill Gates—has graced the cover of Fortune more than a dozen times. And it’s no wonder: Buffett has been a towering figure in both business and

investing for much of his—and Fortune’s—95 years on earth. (The magazine first hit newsstands in February 1930; Buffett was born that August.) As Geoff Colvin writes in this issue, Buffett’s investing genius manifested early, and he bought his first stock at age 11. By Colvin’s calculations, over the 60 years since Buffett took control of his company, Berkshire Hathaway, its returns have outpaced the S&P 500 by more than 100 to one.

Buffett has always had a special relationship with Fortune, particularly with legendary writer and editor Carol Loomis, who profiled him many times, and to whom he broke the news of his paradigm-shifting moves in philanthropy in 2006 and 2010. The end of an era is upon us, as Buffett on Dec. 31 will step down from his role as Berkshire’s CEO. We’re grateful to have been along for the ride.

Cover photographs by David Yellen (2009), and Art Streiber (2010)

Cover photographs by Michael O’Neill (2003), and Ben Baker (2006)

Cover photographs by Michael O’Neill

Cover photographs by Alex Kayser (1986) and Michael O’Neill (1998)

Business

Kimberly-Clark exec says old bosses would compare her to their daughters when she got promoted

Published

2 hours agoon

December 7, 2025By

Jace Porter

Women have their own unique set of challenges in the workforce; the “motherhood penalty” can set them back $500,000, their C-suite representation is waning, and the gender pay gap has widened again. One senior executive from $36 billion manufacturing giant Kimberly-Clark knows the tribulations all too well—after all, she’s one of few women in the Fortune 500 who holds the coveted role.

Tamera Fenske is the chief supply chain officer (CSCO) for Kimberly-Clark, who oversees a massive global team of 22,665 employees—around 58% of the global CPG manufacturer’s workforce. She’s in charge of optimizing the company’s entire supply chain, from sourcing raw materials for Kimberly-Clark products including Kleenex and Huggies, to delivering the final product into customers’ shopping carts.

It’s a job that’s essential to most top businesses operating at such a massive scale; around 422 of the Fortune 500 have chief supply chain officers, according to a 2025 Spencer Stuart analysis. However, most of these slots are awarded to white men; only about 18% of executives in this position are women, and 12% come from underrepresented racial and ethnic backgrounds. It’s one of the C-suite roles with the least female representation, right next to chief financial officers, chief operating officers, and CEOs.

In fact, Fenske is one of just 76 Fortune 500 female executives who have “chief supply chain officer” on their resumes. However, the executive tells Fortune it’s an unfortunate fact she “doesn’t think about” too often—if anything, it motivates her further.

“Anytime someone tells me I can’t do something, it makes me want to work that much harder to prove them wrong,” Fenske says.

The first time Fenske noticed she was one of few women in the room

Fenske has spent her entire life navigating subjects dominated by men—something she didn’t even consider until college.

Her father, aunts, uncles, and grandfather all worked for Dow Chemical, so she grew up in a STEM-heavy household. Naturally, she leaned into math and science as well, eventually pursuing a bachelor’s in environmental chemical engineering at Michigan Technological University. It was there that her eyes first opened to the reality that she was one of few women in the room.

“It definitely was going to Michigan Tech, where I first realized the disparity,” Fenske said, adding that there was around an eight-to-one male-to-female ratio. “As you continue through the higher levels and the grades, it becomes even more tighter, especially as you get into your specialized engineering.”

Once joining the world of work, it wasn’t only Fenske who noticed the lack of women in senior roles—some bosses would even point it out.

The Fortune 500 boss is paying it forward—for both men and women

After Fenske graduated from Michigan Tech, she got her start at $91 billion manufacturer 3M: a multinational conglomerate producing everything from pads of Post-It notes to rolls of Scotch tape. Fenske was first hired as an environmental engineer in 2000. Promotion after promotion came, but all people could seem to focus on was her gender.

“It would come to light when I moved relatively quickly through the ranks. Some of my bosses would say, ‘You’re the age of my daughter,’ and different things like that. ‘You’re the first woman that’s had this role at this plant or in this division,’” Fenske recalls. Over the course of 2 decades, she rose through the company’s ranks to the SVP of 3M’s U.S. and Canada manufacturing and supply chain.

And anytime she was asked about her gender? She’d flip the questions back at them while standing her ground. “I would always try to spin it a little bit and ask them questions like, ‘Okay, so what is your daughter doing?’…I always try to seek to understand where they are coming from, but then also reinforce what brought me to where I am.”

Now, three years into her current stint as Kimberly-Clark’s CSCO, the 47-year-old is paying it back—but not just to the women following in her footsteps.

“I never saw myself as necessarily a big, ground-breaker pioneer, even though the statistics would tell you I was,” Fenske says. “I tried to give back to women and men, to be honest. Because I think men [are] one of the strongest advocates for women as well. So I think we have to teach both how to have that equal lens and diverse perspective.”

Business

SpaceX to offer insider shares at record-setting $800 billion valuation

Published

11 hours agoon

December 6, 2025By

Jace Porter

SpaceX is preparing to sell insider shares in a transaction that would value Elon Musk’s rocket and satellite maker at as much as $800 billion, people familiar with the matter said, reclaiming the title of the world’s most valuable private company.

The details, discussed by SpaceX’s board of directors on Thursday at its Starbase hub in Texas, could change based on interest from insider sellers and buyers or other factors, said some of the people, who asked not to be identified as the information isn’t public. SpaceX is also exploring a possible initial public offering as soon as late next year, one of the people said.

Another person briefed on the matter said that the price under discussion for the sale of some employees and investors’ shares is higher than $400 apiece, which would value SpaceX at between $750 billion and $800 billion. The company wouldn’t raise any funds though this planned sale, though a successful offering at such levels would catapult it past the record of $500 billion valuation achieved by OpenAI in October.

Elon Musk on Saturday denied that SpaceX is raising money at a $800 billion valuation without addressing Bloomberg’s reporting on the planned offering of insiders’ shares.

“SpaceX has been cash flow positive for many years and does periodic stock buybacks twice a year to provide liquidity for employees and investors,” Musk said in a post on his social media platform X.

The share sale price under discussion would be a substantial increase from the $212 a share set in July, when the company raised money and sold shares at a valuation of $400 billion. The Wall Street Journal and Financial Times earlier reported the $800 billion valuation target.

News of SpaceX’s valuation sent shares of EchoStar Corp., a satellite TV and wireless company, up as much as 18%. Last month, EchoStar had agreed to sell spectrum licenses to SpaceX for $2.6 billion, adding to an earlier agreement to sell about $17 billion in wireless spectrum to Musk’s company.

Subscribe Now: The Business of Space newsletter covers NASA, key industry events and trends.

The world’s most prolific rocket launcher, SpaceX dominates the space industry with its Falcon 9 rocket that lifts satellites and people to orbit.

SpaceX is also the industry leader in providing internet services from low-Earth orbit through Starlink, a system of more than 9,000 satellites that is far ahead of competitors including Amazon.com Inc.’s Amazon Leo.

Elite Group

SpaceX is among an elite group of companies that have the ability to raise funds at $100 billion-plus valuations while delaying or denying they have any plan to go public.

An IPO of the company at an $800 billion value would vault SpaceX into another rarefied group — the 20 largest public companies, a few notches below Musk’s Tesla Inc.

If SpaceX sold 5% of the company at that valuation, it would have to sell $40 billion of stock — making it the biggest IPO of all time, well above Saudi Aramco’s $29 billion listing in 2019. The firm sold just 1.5% of the company in that offering, a much smaller slice than the majority of publicly traded firms make available.

A listing would also subject SpaceX to the volatility of being a public company, versus private firms whose valuations are closely guarded secrets. Space and defense company IPOs have had a mixed reception in 2025. Karman Holdings Inc.’s stock has nearly tripled since its debut, while Firefly Aerospace Inc. and Voyager Technologies Inc. have plunged by double-digit percentages since their debuts.

SpaceX executives have repeatedly floated the idea of spinning off SpaceX’s Starlink business into a separate, publicly traded company — a concept President Gwynne Shotwell first suggested in 2020.

However, Musk cast doubt on the prospect publicly over the years and Chief Financial Officer Bret Johnsen said in 2024 that a Starlink IPO would be something that would take place more likely “in the years to come.”

The Information, citing people familiar with the discussions, separately reported on Friday that SpaceX has told investors and financial institution representatives that it’s aiming for an IPO of the entire company in the second half of next year.

Read More: How to Buy SpaceX: A Guide for the Eager, Pre-IPO

A so-called tender or secondary offering, through which employees and some early shareholders can sell shares, provides investors in closely held companies such as SpaceX a way to generate liquidity.

SpaceX is working to develop its new Starship vehicle, advertised as the most powerful rocket ever developed to loft huge numbers of Starlink satellites as well as carry cargo and people to moon and, eventually, Mars.

Bernard Arnault pays homage to late Frank Gehry

Handbag brand Abel Richard makes global debut in Miami

Eileen Higgins to campaign in Miami with Ruben Gallego ahead of Special Election for Mayor

Trending

-

Politics8 years ago

Politics8 years agoCongress rolls out ‘Better Deal,’ new economic agenda

-

Entertainment8 years ago

Entertainment8 years agoNew Season 8 Walking Dead trailer flashes forward in time

-

Politics8 years ago

Politics8 years agoPoll: Virginia governor’s race in dead heat

-

Entertainment8 years ago

Entertainment8 years agoThe final 6 ‘Game of Thrones’ episodes might feel like a full season

-

Entertainment8 years ago

Entertainment8 years agoMeet Superman’s grandfather in new trailer for Krypton

-

Politics8 years ago

Politics8 years agoIllinois’ financial crisis could bring the state to a halt

-

Business8 years ago

Business8 years ago6 Stunning new co-working spaces around the globe

-

Tech8 years ago

Tech8 years agoHulu hires Google marketing veteran Kelly Campbell as CMO